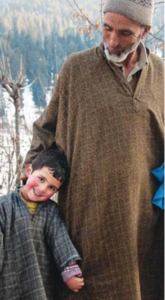

In a significant development, the lives of Kashmiri refugees in Pakistan-administered Kashmir are poised for a positive transformation. Raja Aurangzeb Khan, a seasoned 60-year-old refugee who left his home in Kupwara district in 1990, expressed optimism about a brighter future for his family. ‘I am optimistic that we will soon get rid of corrugated tin shelters and tents, and we may finally own our homes,’ he said. Khan currently resides with his five daughters and two sons in one of the refugee camps in Chalha Bandi, near Muzaffarabad city, on the bank of the river Neelum, representing just one of the dozens of families facing similar challenges in that camp.

The commitment of the Pakistani government to addressing the refugee crisis is evident, with the approval of Rs. 3 billion for the construction of 750 houses inthe first phase. This move is set to benefit 750 Kashmirirefugee families, bringing a sense of stability and permanence to their lives. A government official disclosedthat the disbursement of funds, totaling Rs. 3,880,000per family, will be provided in three installments. Notably,the decision to have refugees construct their own houses was made to ensure that every penny is utilised efficiently, with no wastage. This hands-on approach aimsto maximise the impact of the financial assistance provided, ensuring it directly benefits the families in need.

The rehabilitation department reports that there are currently 8,158 Kashmiri refugee families in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, totaling 44,682 individuals whosought refuge from the atrocities of the Indian army.These families are spread across 13 camps, with anadditional 2,800 families comprising 14,566 individualsliving outside the camps, facing heightened vulnerability.In a strategic move, the government is prioritising themost vulnerable families in the first phase, with plansto extend support to others in subsequent phases. Thisphased approach ensures that those who need assistance the most receive it promptly.

Raja Aurangzeb Khan shared his harrowing experiencesin Indian-administered Kashmir, recounting instances offrequent raids by the Indian army. ‘They would cordon ourvillage at night, ask men, women, and children to comeout of their homes, line them up, and hold an Identity parade.’ His personal ordeal involved being picked up 5.6times, enduring physical abuse, and living in constantfear. ‘They would blindfold me, dump me in a vehicle,and take me away to a nearby army camp,’ Khan said,adding that the Indian army would tie his hands from theback, beat him with sticks, rifle butts. ‘They would abuseme. They would also throw hot water on me and sometimes open my mouth and put hot tea in it.’

‘I spent three months on trees before I crossed the Line of Control in August 1990, leaving my wife and two daughters behind,’ Khan revealed. His family reunited with him after three challenging months, highlighting the immense sacrifices made by these refugees in the pursuit of a safer and more secure life.

These people receive a monthly guzara (subsistence) allowance of Rs 3,500 per head from the government of Pakistan, and some do private or government jobs to feed their families. Many are jobless as there is already more than a 14 per cent unemployment rate in Azad Kashmir. But their monthly income is not enough to pay electricity and gas bills, children’s schooling expenses, and run the household kitchen.

Raja Aurangzeb Khan faces the challenge of providingeducation to his children amidst inflation and a modestincome. His eldest son works as an electrician with amiddle-class education, holding a private job. Anotherson, a graduate, repairs mobile phones, while a thirdson, also a graduate, is engaged in a temporary positionin civil defense. One of his daughters is pursuing a Ph.D.,and two other daughters are enrolled in master’s programs at AJK University. Khan expressed the difficultyof ensuring his children’s education, highlighting that heworked as a labourer to fund their education.

Raja Basharat Khan, currently 44-year-old, resides inthe same refugee camp with his family and is optimisticabout their upcoming move to new homes. ‘I am hopefulthat we will be in our new homes, thanks to the government of Pakistan,’ he expressed. Khan mentioned thathis children were thrilled upon learning about the government of Pakistan’s initiative to construct new homes for them.

Bashrat Khan, employed in a private job, expressed that due to his limited income, he couldn’t envision building a home on his own. He mentioned his monthly earnings, combining guzaras (allowance) and daily income, ranging between Rs. 35,000 to Rs. 40,000.

Living with his wife and four children, the eldest daughter is a grade 9 student, the eldest son is in grade 6, the younger one is in grade 3, and the youngest son is in nursery. ‘It is very challenging to live in temporary shelters made of corrugated sheets and wood, lacking sufficient space, proper sewerage, and safe drinking water. Whenever there is rain or wind, the roofs of our shelters get damaged,’ Khan explained. Originally from a village in Kupwara, a northern district in Indian-administered Kashmir, Basharat Khan, along with his parents and siblings, left their home in 1990 and sought refuge in Azad Kashmir when he was a primary school student. Khan explained that they fled because staying there was no longer safe.

He recalled the harrowing experiences they faced at the hands of the Indian army. ‘Soldiers would frequently conduct cordon and search operations, subjecting villagers to brutality, regardless of age or gender. Schools and colleges were raided, and teachers were assaulted under false accusations of supporting militants.’ He said that the situation escalated when the Indian army handed a list of boys from Basharat’s village to his father, demanding their surrender. These boys, including his brother and cousins, were subjected to torture while in custody. They were freed in weeks and months. Fearing for their lives and honour, approximately 350families from their village sought refuge in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, leaving behind their homes, businesses, land, and cattle.

As the government of Pakistan takes steps to construct new homes for refugees, there is a tangible sense of hope and optimism among these families. The construction of new homes represents more than just a physical structure; it symbolises a chance at a secure and stable future, free from the hardships they faced in the past.

In the face of adversity, these Kashmiri refugees exhibit resilience, determination, and a shared belief that the new homes being constructed will not only provide shelter but also mark the beginning of a brighter chapter in their lives. The journey toward stability and permanence is underway, guided by the collective efforts of the Pakistani government and the unwavering spirit of the Kashmiri refugees.

The writer is a journalist from Muzaffarabad.