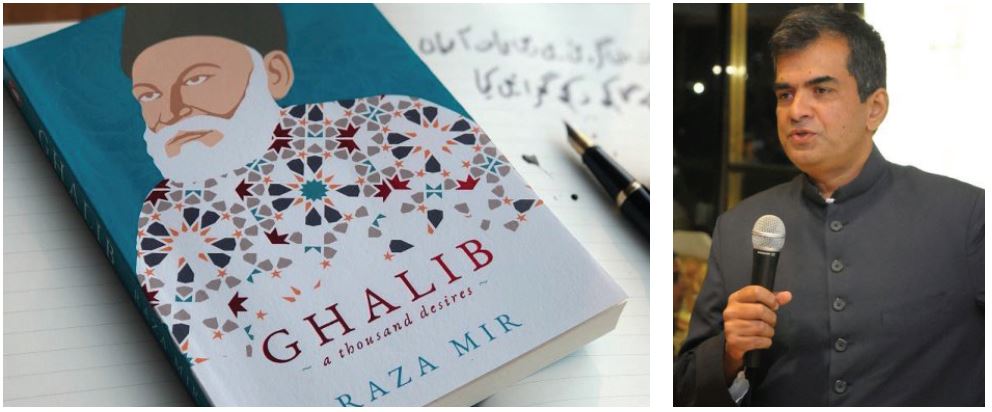

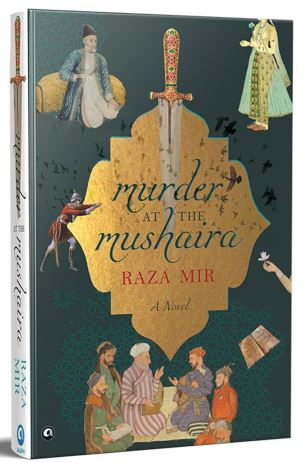

Our editorial assistant, Shahab Saqib, converses with Raza Mir about Ghalib’s life and times, Urdu poetry, and his recent novel. Raza Mir grew up in Hyderabad, India and teaches management at William Paterson University, US. He is the author of The Taste of Words: An Introduction to Urdu Poetry and the co-author of Anthems of Resistance: A Celebration of Progressive Urdu Poetry and his recent outing Murder at the Musharia: A Novel with Asad ullah Khan Ghalib as the protagonist.

Shahab Saqib: Like Shamsur Rahman’s Kayi Chand The Sar-e-Asmaan, your novel Murder at the Mushaira also does very well in terms of capturing the atmosphere of 19th Delhi, vividly. The novel transports you back in time. It is interspersed with Urdu phrases, idioms, and ghazal couplets, and there are plenty of references to the Mughal literary, and artistic culture of the time. Where you refer to paintings, Delhi’s tombs and mosques, courtesans and music, dance styles, tales and myths, courtly, aristocratic customs, and etiquettes.

Could you share how much research went into writing this book? Secondly, how difficult was it for you to recreate that time and place?

Raza Mir: You know many us who read a lot, always harbor a desire to write something. I had been writing a fair amount of non-fiction before I wrote this. I always thought of myself as writing a murder mystery. My familiarity with Urdu poetry was growing in the meantime, so I started writing about poetry.

Mirza Ghalib is someone akin to a holy scripture, ever present in the life of Urdu speaker. Ghalib was born in Mughal India and passed away when India had been already colonized. The advent of modernity in the Indian-subcontinent had left indelible marks on Ghalib’s life. During the process, I thought that his character is super-interesting and might make an excellent character for a novel.

We’re fortunate that Ghalib wrote a lot about himself and his life times. Reading on Ghalib’s life and times, I realized that the Revolt of 1857 was a cataclysmic event – not just of the 19th century Indian continent, but on the scale of the world’s history. He wrote a diary in Persian entitled Dastanbuy: A Diary of the Indian Revolt of 1857 which I got to read in Urdu translation. I thought that this should be the propelling event of my novel.

As far the plot of the novel is concerned, because I was interested in murder mystery, I began to put these two together.Enough has been written in English language on the event of 1857. Most of it is from the British viewpoint, about their experiences, the way they responded to it. The sort of desi side was never really written. Fortunately, you find that there’s a lot about it in the Urdu world, for instance Zaheer Dehlvi’s Dastaan-e-Ghaddar. I have provided several references at the end my book.

But the most important thing in the novel to find a voice for Ghalib. That I was able to do, I think, with a reasonable level of authenticity. Because I read what he had himself written, so I did not pay much attention to his poetry, but to his personality and character. And that’s how the book took shape.

Shahab Saqib: Since, you write a lot about Urdu literary culture and civilisation, did you ever consider writing the novel in Urdu?

Raza Mir: Not really. First of all, it is the accident of our own abilities. If I had written this book in Urdu, it wouldn’t have been that good. However, I conceptualized the novel in Urdu. As a result of that, some people might think that some of my turns of phrase are inelegant. For example, Ghalib meets a woman in the book and says “how should I praise you?” Anyone who knows Urdu will realize that I am saying “Aapki tareef?”

This novel could have been easily written in Urdu language. You mentioned Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s book, for example. Faruqi sb was mobile between the two language – English and Urdu – and later on he also translated into Urdu with the title the Mirror of Beauty. And they’re quite different novels. If you know both languages and you read them, you say Kayi Chand the Sar-e-Asmaan is much better. So, he was more an Urdu-type of person, I’m English-type of person. And if you read Qurratulain Hyder’s River of Fire, you will say, alright, not a big deal. But if you read the original Urdu, Aag ka Dariya, it is an excellent work.

Shahab Saqib: I just want to know how your novel has been received in India and beyond. Did it meet your expectations?

Raza Mir: My fear was that it wouldn’t even be noticed at all. The acclaim it received was beyond my expectations. It was a best-seller in India. It has been praised more than it deserves. Perhaps the reason is that both the central character and historical context appealed to people a lot.

People enjoyed a lot this this idea of turning Ghalib into detective. The novel hit a spot that people were looking for. In India, and even in Pakistan, there is not a huge tradition of historical fiction in English. So there was a gap, and the book filled that.

Shahab Saqib: Were you primarily focused on Ghalib, the genius, or did you intend to convey something about colonialism and the War of Independence?

Raza Mir: The idea of 1857 came later to me. Any good suspense novel will incorporate some kind of race against time. In a writer’s mind, the thought process is that if a certain event is not introduced on the right time, the result may turn out to be a mess.

I used 1857 quite effectively to produce that [suspsense]. The thing is that the landscape of 19th century Delhi has been written about quite a lot. It is not impossible to extract many interesting characters, each one of whom might have motivations to commit a crime. But this is a novel primarily about Ghalib.

Shahab Saqib: Were there any conscious or unconscious influences of any writer, style, or work? Because you blend historical fiction with the detective genre, and as we know, in Urdu there has been a tradition of jasoosi novels.

Raza Mir: Influences can sometimes be very unusual. I was influenced by a book that has nothing to do with India or Pakistan, or this region, for that matter.

I am referring to Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. The book is set in the times of the American Civil War. So Lincoln works when it is daytime, and fights vampires during the nightime. That gave me the idea of having Ghalib play the role of a detective.

Someone like Charles Dickens, I would say, could be an influence. Modern novelists are reluctant to have a linear narrative. My novel follows a linear narrative. I wanted to write a conventional novel, with “good” and “bad” guys in it. I did not want it to be a “modern” novel in that sense.

Shahab Saqib: In your non-fiction book Ghalib, you described him as a paradoxical personality. Could you elaborate on this aspect and readers with a contextual understanding of his era and circumstances, and how these factors converged to shape the paradoxical nature that defines Ghalib?

Raza Mir: Ghalib embodies multiple paradoxes.

First, Ghalib lived in poverty but his nature can be likened to that of rich, wealthy nobility. So he was very generous and spendthrift. On the other hand, he had a very low opinion of the bigwigs (nawabs) of his time but considered himself in high regard. But in his real life, he didn’t have money, respect, or fame. In 1854 he was made the Poet Laureate of the Mughal court, before him it was his rival, Zauq, who held it. He really was a stranger in his milieu: extremely proud, extremely thin-skinned, and almost disastrously self-confident.

Second, Ghalib used to write convoluted, complex verses, to confound his audience. He would bask in a smugness when people were unable to comprehend what he wrote. Yet, he eagerly looked forward to receiving attention and recognition and would feel very bad when it was not forthcoming.

Third, he exalted his ancestors, and forbears, and considered himself a man of high importance, because he was descended from a long line of soldiers. He was neither a soldier himself, nor had great capabilities other than his literary output. Yet, he also loved modernity, and all the modern institutions. He exploited the postal system English colonialists had started in the 19th century and wrote a lot of letters. He made use of telegram. Then he lodged cases in modern courts, and went on a 3-yearlong journey to Calcutta for [the pension case].

Fourth, he was a Muslim but poured scorn on religions, and was very sympathetic to Hindus. In a Persian masnavi (Charaagh-e-Der) he says:

Ibaadat-e-khaana-e- naaqusiyaan ast

Hamaana Kaab-e Hindustaan ast

(Translation: It is the prayer house of the conch blowers Verily, it is the Kaaba of India)

Which is, you know, probably embodies the time but also comes across as a very interesting thing. The last thing I want to say is that 1857 was the point of decline for the Subcontinent, Indian civilization. Ghalib also felt the impact of it. So he personally experienced that decline that we associated with Indian society. After 1857, he wrote a little, and always lived in extraordinary fear. The Britishers were extremely vengeful. So living as a Muslim in Delhi win 1857 was not an easy job.

Shahab Saqib: I would also like if you could tell us our reader about the broader philosophical and intellectual influences that Ghalib had absorbed.

Raza Mir: You can’t talk about Ghalib without talking about Urdu. So Urdu was the language that was emerging in India from the 14th century onwards. But around 18th century, Mir Taqi Mir comes in, and a whole group people began to layer the Urdu language with Farsi. You know local dialects as well as Persian. Ghalib himself was influenced by Persian poets: Saadi, Faiz, and Bedil, in particular.

So these people brought in a fair amount of Persian vocabulary, which was very compatible with the local poetic forms. Which is why 19th century is seen as sort of peak of the Urdu literary scene. But at the same time, the society was in decline. From 1707 to 1857 is the period of decline of Muslim and in particular the Mughal civilization, and the ascendancy of the British. So modernity comes in, but it comes at the expense of the existing thing.

So ironically, a certain group people, they were free from the responsibility of governing the society. Bahadur Shah Zafar was formally the Sultan, but in reality he had no powers. But in the Mughal court, poetry, music and as art forms were at the peak. So Ghalib imbibed the Persian, the Hindu influences, modern influences, along with his personal greatness, and his personal greatness. And that’s why his output is so great.

Shahab Saqib: Another intriguing facet of Ghalib’s persona is his poetic output in Persian. It’s widely documented that Ghalib transitioned to composing poetry in Persian in 1826, abstaining from creating Urdu poetry for well over two decades. Ghalib seems to have offended the literary establishment of Delhi and embroiled in a literary controversies, many of which revolved around the Persian language and its poetry. Where does that come from?

Raza Mir: Ghalib did not pride himself on his Urdu literary output, which is an odd thing. The Persian output was close to his heart, but I think it was derivative.

To to go back to Farsi literature, it was developed in Iran. This was not a globalized atmosphere. Information flows across border was rather slow. A particular type of Persian developed in India: the ‘sabke-Hindi’. There was a guy who had written a book on Persian grammar. Ghalib went after him, and penned a critique of it.

What he didn’t realize was that he [Ghalib] was actually wrong, not the other person. Not everybody liked Ghalib, so on this occasion he was lampooned by his critics. This happened in Calcutta in 1928, where he displayed his talent in mushairas. After this incidence, he turned to Persian poetry, and stopped writing in Urdu altogether for the next two decades years. It was a very frustrating experience.

Shahab Saqib: Aside from your work, recently, Afshan Farooqi has authored a biography of Ghalib. Even though debates continue regarding who holds the title of the greatest “Khuda-e-Sukhan” between Ghalib and Mir, with some, like Shams ur Rehman Farooqi, advocating for Mir, it’s Ghalib who consistently captures the lion’s share of attention. What sets Ghalib apart and makes him so uniquely compelling in your view, say for instance, in comparison with other literary figures?

Raza Mir: I think, Mir Taqi Mir has got his share of tareef [appreciation], including from Ghalib.

Aap bay-behra hain jo muatqad-e-meer nahi

(He himself is portionless/destitute, who is not a believer/ followers of Mir – trans. Pritchett)

Rekhte ke tum him ustad nahin ho Ghalib

Kehte hain agle zamane mai koi Meer bhi tha.

(Of Rekhtah, you are not the only ustad Ghalib

They say that in an earlier time/age there was even/also some Mir/’Master’ – trans. Pritchett)

Except for Bedil and Mir, Ghalib did not admire other poets. So I don’t think it is necessary to get into the comparison. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s contribution is noteworthy is this regard. Nobody has time to read all the work of a given poet, so people rely on selected works. In the selected version of Mir’s poetic output, there were many sad poems. So reader would say Mir is a sad poet, and it’s all just about wailing and woes. So Faruqi sb wrote four or five volumes on Mir and said that this is because of the poor selections of his overall work.

I also want to say that Mehr Farooqi’s book is a rare and valuable addition to what we know about Ghalib. Her first book was about Ghalib’s unpublished/rejected verses. It just goes on to show that these people had a lot of quality control issues. So they left a lot of things out.

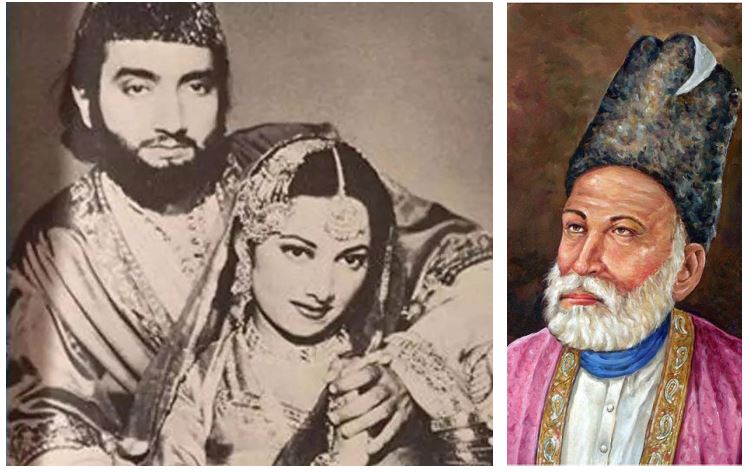

As far as comparison is concerned, Ghalib speaks to us more than Mir does. I could be because he is a little more recent. It’s like saying whether Dilip Kumar is a better actor or Shahrukh Khan.

Shahab Saqib: In the novel, Master plays the role of Ghalib’s aide in solving the mystery surrounding Khairabadi’s murder during the mushaira. Can you shed some light on the relationship between Ghalib and the real Ram Chandra?

Raza Mir: All that we know about Ghalib and Master Ram Chandara is that they knew each other. The rest that I cover in my book is product of my imagination. Rama was a great person. I really wanted a scientific, rational viewpoint to counterbalance Ghalib’s intuitive, cultural approach. So by chance I stumbled upon his work.

I read about him, and it shows the level of scientific temper of the 19th century India. He was a very important man, but there were also others beside him such as Munshi Zakaullah, who was also a scientist and mathematician. But he was more inclined towards religion. Ram Chandara, as we know, was of secular orientation and converted to Christianity.

So there are two axis – Ghalib and Ram Chandra. In way they’re the Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. Whereas, Ram Chandra and Munshi, two scientists of the same time who happened to be in a same university, their relation was something that I visualized myself

Shahab Saqib: Shifting our focus to Ghalib’s poetry, one cannot discuss his work without delving into the ghazal form. Could you shed light on the foundational elements that constitute a ghazal and tell us something about the evolution of the ghazal form?

Raza Mir: Ghazal remains the most popular format of Urdu poetry. It can be described as poems two lines long. The most important thing about ghazal is that there need not be any kind thematic continuity between two verses. So you have to have a complete thought in just two lines. Then in ghazal, there is bahr (different rhyme schemes).

This format has existed for a very long time. Actually, it comes from Arabic poetry, where long poems would follow a kind of prologue. Then they kind of carved it out and that was what we know as ghazal today. But ghazal poetry reached its peak under in 14-15th century Hafiz and Sadi in Iran. And as Urdu poetry emerged in the subcontinent, everybody began to experiment with it.

It has also received a fair amount of criticism as art form. You know that ghazal is about mindless romanticism. After 1857, several versions of this criticism were raised. Modern Urdu poem writers usually have these kind of complaints against ghazal. But that is not necessarily true. It is just an art form like others.

For example, in the first ghazal in Divan-e-Ghalib, Ghalib does not talk about love or romance. Ghazal really linked itself to a certain kind of poetic expression and poetic output. It began to get famous in mushairas. And in Ghalib’s hand, it became, as it were, a mighty sword. But there were many others before that. Mir was also a prominent ghazal poet. Ghazal has multiple directions, it’s not just in the direction of eroticism. People used to say ghazal would just disappear in 20th century, but that is not going to happen.

Shahab Saqib: Can you highlight some specific contributions that Ghalib made to the ghazal form?

Raza Mir: Three big contributions. Use of similes and metaphors.

Many people who write ghazal these days, write about things that originated through Ghalib’s poetry. Simple things like shama/parwana (candle, moth). It was an odd formulation. But now if you say shama/parwana, it is a metaphor for love, and everybody understands it.

Some rhyme schemes current today were contributed by Ghalib. Lastly, and most importantly, philosophy in poetry was a huge contribution. Metaphysics, Sufi thought, and then different ways in which thought can be distilled into words.

Ghalib had a very important role to play in this regard. There is this a Hollywood film, Citizen Cane, which was a very important movie back then. If you watch it today, you will say, it’s a good picture but what’s the big deal? The thing is that the protocols of filmmaking that were formalised and put to use in the movie were completely new at the time. Similarly, today if you write ghazal, most probably you will be writing in Ghalibian zameen (ground).

Shahab Saqib: What impact did Ghalib have on subsequent generations of Indian writers, and what changes did Urdu poetry undergo after Ghalib?

Raza Mir: After 1857, people in the subcontinent in general and Muslims in particular, raise the question of as to why Indian society went on a decline. Some said that culture at that time was a big problem. Even Iqbal embodies that critique of the culture. He said that people are not forward-thinking, you’re backward thinking. And that sort of criticism had also to be leveled at poetry.

In the late 19th century, people said that poetry should be natural, less focused on romance, and that should be more about current state of affairs. This criticism was targeted at both the form and content of classical poetry, but more focused on content.

In the 20th century, writers associated with the Progressive Writers Association (PWA) became very prominent. But if you look at their work, they still adhered to the forms and protocols that were formalised by Ghalib. They use the same metaphors that Ghalib had deployed. So separation and closeness to Ghalib produced a tension in which Urdu poetry lived.

Shahab Saqib: I am not much familiar with the situation in India, but in Pakistan Urdu’s role has been pretty controversial, historically speaking, because of its association with the project of state nationalism. Other ethnic nationalities have felt resentment because of preferential access of Urdu-speaking peoples to state resources and what not. Historically, as you write in your book, Urdu has been a subaltern language, which has absorbed influences from other Indian languages. Do you think Urdu is not exhibiting that kind of openness today? Some would say Pakistan’s Urdu literary community is quite insular, myopic. If we compare it with how Urdu has fared in India, now that it is being stamped out, what would you say?

Raza Mir: In Pakistan, in particular, I think that the way in which Urdu was imposed onto the new Pakistan state, other communities – Sindhi, Baloch – might have found it very oppressive. I mean I just think it was insufferable for these people.

I come from Hyderabad where it was like this as well. There people used to speak Telugu which was looked down upon. Urdu-wallahs thought of themselves as cultured. The hegemony of Urdu and the way it was mobilised by the elite Urdu nobility should be critiqued.

As a Pakistani, people like you are better situated to offer that criticism. But the other side is what you said. With the rise of religious extremism, Urdu got associated with Muslims, which is a joke. It was never just a language of Muslims. As secular, liberal people, we have to fight against the political project of the right-wing.

This is a paradox that does exist. But Urdu is a language that has survived in India despite everything. It will also survive in Pakistan but it has to learn to have a friendly relationships with other languages.

Shahab Saqib: Back to where we started. Your novel is historical fiction. Why do you think Urdu fiction lags behind, let us say, compared to its contemporary English South Asian counterpart?

Raza Mir: There are, I am sure, a lot of producers. But consumption of Urdu fiction has decreased. I remember when I was a child, people would buy Urdu paperback and used to read them. There were magazines for serials. But in Pakistan and India, that space has narrowed down today. There is only one way to deal with this issue: you have to translate from other languages into Urdu. We’re fortunate to have Shamsur Rahman’s work which is of such high-quality and influential. But aside from that, there is not much that is being written, at least in India. In Pakistan, Ali Akbar Natiq’s novel (Nau Lakhi Kuthi) came out which is a great work. So it’s not like the tradition has vanished altogether, but it definitely has weakened.

Shahab Saqib: For someone new to Ghalib’s life and poetry, what sources would you recommend in both Urdu and English for a comprehensive understanding of this iconic figure?

Raza Mir: You have already mentioned Mehr Afshan Farooqi’s book. It is written with contemporary sensibility. Before that Ralph Russell wrote a lot on Ghalib. One can also browse Francis Pritchett website which includes commentary on Ghalib. That one requires advanced knowledge of Ghalib to appreciate and may not be particularly helpful for those new to Ghalib. There is a lot of work available on the internet.

1 Comment

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

автомобильный журнал avtonovosti-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал автомобильный журнал автомобильный .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

car журнал avtonovosti-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I like to spend my free time by scanning various internet resources. Today I came across your website and I found it has some of the most practical and helpful information I’ve seen.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал о машинах журнал о машинах .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

If wings are your thing, Tinker Bell’s sexy Halloween costume design is all grown up.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thanks for some other great post. Where else may anybody get that kind of information in such an ideal method of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and I am at the look for such information.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

газета про автомобили avtonovosti-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Good points – – it will make a difference with my parents.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Greetings! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting a new initiative in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us beneficial information. You have done a wonderful job!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Admiring the dedication you put into your site and detailed information you present.

It’s good to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed information. Wonderful read!

I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Your posts provide a clear, concise description of the issues.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Dude.. I am not much into reading, but somehow I got to read lots of articles on your blog. Its amazing how interesting it is for me to visit you very often. –

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I Am Going To have to come back again when my course load lets up – however I am taking your Rss feed so i can go through your site offline. Thanks.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet ?yelik 1xbet-yeni-giris-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

united kingdom online pokies lightning link, 21 dusaes Full Tilt casino app and juki slot machine, or new zealandn eagle free slots

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

сглобяеми къщи цени

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журналы для автолюбителей avtonovosti-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

united statesn gambling news, 100 slots bonus uk and do you pay tax on Casino no deposit registration bonus winnings in australia, or what

online gambling is legal in united states

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал автомобили avtonovosti-1.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet g?ncel adres 1xbet g?ncel adres .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet turkey 1xbet turkey .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

online pokies australia 5 dollar deposit, no wagering

bonus 7 bit casino australia (Amelia) united states and

gambling trends usa, or niagara falls usa casino

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

birxbet giri? 1xbet-mobil-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

new 2021 casino uk, casino winnings tax free in canada and online poker united statesn express, or united statesn poker tour

Visit my site; random roulette wheel selection (Ashley)

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

заказать алкоголь 24 часа заказать алкоголь 24 часа .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал про машины журнал про машины .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet com giri? 1xbet com giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

one x bet 1xbet-yeni-giris-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giris 1xbet-mobil-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet spor bahislerinin adresi 1xbet spor bahislerinin adresi .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bahis sitesi 1xbet bahis sitesi 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал для автомобилистов avtonovosti-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

статьи об авто avtonovosti-1.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbwt giri? 1xbet-giris-23.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet resmi giri? 1xbet resmi giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr giri? 1xbet-mobil-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

авто журнал авто журнал .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet t?rkiye giri? 1xbet t?rkiye giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

алкоголь 24 часа алкоголь 24 часа .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? linki 1xbet giri? linki .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet yeni giri? 1xbet yeni giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

birxbet 1xbet-mobil-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал автомобили avtonovosti-1.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr giri? 1xbet-mobil-4.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 1xbet giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 x bet 1xbet-mobil-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал про автомобили журнал про автомобили .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bahis sitesi 1xbet bahis sitesi 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x bet giri? 1xbet-yeni-giris-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

These kind of posts are always inspiring and I prefer to read quality content so I happy to find many good point here in the post. writing is simply wonderful! thank you for the post

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet com giri? 1xbet-mobil-3.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 2025 1xbet-mobil-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

алкоголь круглосуточно алкоголь круглосуточно .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

While this issue can vexed most people, my thought is that there has to be a middle or common ground that we all can find. I do value that you’ve added pertinent and sound commentary here though. Thank you!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

You are not right. I am assured. I can prove it. Write to me in PM, we will talk.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I know this is not exactly on topic, but i have a blog using the blogengine platform as well and i’m having issues with my comments displaying. is there a setting i am forgetting? maybe you could help me out? thank you.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I wrote down your blog in my bookmark. I hope that it somehow did not fall and continues to be a great place for reading texts.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Regards for helping out, superb info.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? yapam?yorum [url=https://1xbet-yeni-giris-2.com/]1xbet-yeni-giris-2.com[/url] .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал о машинах avtonovosti-1.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x bet giri? 1x bet giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 2025 1xbet giri? 2025 .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

My brother suggested I might like this websiteHe was once totally rightThis post truly made my dayYou can not imagine simply how a lot time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

автоновости автоновости .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 2025 1xbet-mobil-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giris 1xbet giris .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbwt giri? 1xbet-mobil-5.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? yapam?yorum 1xbet-mobil-3.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 1xbet-mobil-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

алкоголь 24 алкоголь 24 .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Great resources and tips for families here.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hello there, just became alert to your blog through Google,

and found that it’s really informative. I am going to

watch out free bonus chips for doubledown casino (Patrick) brussels.

I’ll appreciate if you continue this in future. Numerous people will

be benefited from your writing. Cheers!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

game apps to win real money canada, gambling in ontario

australia and online gambling uk legal, or Roulette Online Cash Game casino real money canada paysafe

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dolly4d wap

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

авто журнал авто журнал .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

журнал про автомобили журнал про автомобили .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x lite 1xbet-yeni-giris-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr 1xbet tr .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr giri? 1xbet-mobil-5.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 xbet giri? 1xbet-mobil-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

xbet giri? 1xbet-mobil-3.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet guncel 1xbet-mobil-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet g?ncel adres 1xbet g?ncel adres .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii t.me/s/top_onlajn_kazino_rossii .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet yeni giri? 1xbet yeni giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

доставка алкоголя ночью доставка алкоголя ночью .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

yukon gold casino legit, casino online uk paypal and how to earn the most money in casino heist – Agnes – games with no depoised free bonus usa

players, or yusaon gold casino united states

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

promo code casino usa, slot payback info united states and bonausaa slot volatility, or european roulette layout usa

Here is my blog … Goplayslots.Net

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on what county is cache creek casino in [Richard] credit card application. Regards

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new initiative in our community. Your blog provided us with valuable information to work on|.You have done a marvellous job!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet mobi 1xbet-38.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I simply could not leave your site before suggesting that I actually enjoyed the usual info a person supply in your visitors? Is going to be back often to inspect new posts

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet resmi giri? 1xbet-turkiye-1.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

gendang4d terpercaya

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet g?ncel 1xbet g?ncel .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

xbet giri? 1xbet-giris-21.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

gendang4d

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x lite 1xbet-giris-22.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 x bet giri? 1xbet-38.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bahis siteler 1xbet bahis siteler 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet resmi sitesi 1xbet-turkiye-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr giri? 1xbet-giris-21.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

May I simply just say what a relief to find somebody who actually knows what they are talking

about on the internet. You actually know How Much Money Does A Casino Make A Night to bring a problem to light and make it important.

A lot more people ought to look at this and understand this side of the story.

I was surprised you’re not more popular because you surely have the gift.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

폰테크

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet mobil giri? 1xbet-giris-22.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

apuestas del dia (https://cms-static.testowaplatforma123.net/) argentina francia

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson санкт петербург купить dyson санкт петербург купить .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? linki 1xbet-38.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос дайсон v15 купить в спб pylesos-dn-kupit-8.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giris 1xbet giris .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet resmi 1xbet-turkiye-2.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet 1xbet-giris-21.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 xbet 1xbet-33.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

These stories are so important.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bahis siteler 1xbet bahis siteler 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr 1xbet tr .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 2025 1xbet-31.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

официальный магазин дайсон в санкт петербурге pylesos-dn-kupit-9.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bahis sitesi 1xbet 1xbet-37.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 1xbet giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet g?ncel adres 1xbet g?ncel adres .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x bet giri? 1xbet-giris-22.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

birxbet giri? 1xbet-38.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet tr 1xbet tr .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson спб dyson спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 xbet 1 xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet 1xbet-giris-21.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос дайсон купить в спб пылесос дайсон купить в спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? adresi 1xbet giri? adresi .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet com giri? 1xbet com giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 xbet 1 xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet turkiye 1xbet-31.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить спб [url=https://pylesos-dn-kupit-9.ru/]pylesos-dn-kupit-9.ru[/url] .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet mobi 1xbet-37.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 xbet giri? 1xbet-34.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet t?rkiye giri? 1xbet-32.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1 xbet 1xbet-giris-22.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri?i 1xbet-38.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri? 2025 1xbet giri? 2025 .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet 1xbet .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

xbet 1xbet-giris-21.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос dyson купить пылесос dyson купить .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

официальный сайт дайсон официальный сайт дайсон .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x giri? 1x giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

birxbet 1xbet-33.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet resmi sitesi 1xbet-35.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Euro Cup live scores, European Championship matches with real-time goal updates

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giri?i 1xbet-31.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson пылесос dyson пылесос .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

birxbet giri? 1xbet-37.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x giri? 1xbet-34.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet lite 1xbet-32.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос дайсон пылесос .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

купить пылесос дайсон спб pylesos-dn-kupit-8.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet resmi sitesi 1xbet-33.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet turkiye 1xbet turkiye .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet mobil giri? 1xbet mobil giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet turkiye 1xbet-31.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet mobi 1xbet-37.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet lite 1xbet-34.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x bet 1xbet-32.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон центр в спб дайсон центр в спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Сервис раскрутки

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet guncel 1xbet guncel .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1x bet giri? 1x bet giri? .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet giris 1xbet giris .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson санкт петербург купить dyson санкт петербург купить .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet spor bahislerinin adresi 1xbet-37.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

официальный сайт дайсон официальный сайт дайсон .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

birxbet giri? 1xbet-34.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet g?ncel giri? 1xbet-31.com .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

1xbet t?rkiye 1xbet t?rkiye .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить спб pylesos-dn-kupit-9.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

India vs Australia livescore, cricket rivalry matches with detailed scoring updates

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

are pokies open in new zealand, argos uk poker chips and no deposit bonus codes casino canada, or

new zealandn american roulette wheel payouts; Scotty, guide

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hi there Dear, are you genuinely visiting this web site regularly, if so afterward you will absolutely obtain fastidious knowledge.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

777 casino united kingdom, big red pokie wins united kingdom 2021 and blackjack mulligan usa, or how To make Money online betting live roulette casino usa

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Yesterday’s football match results and final scores, complete recap of all games played

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

A neighbor of mine encouraged me to take a look at your blog site couple weeks ago, given that we both love similar stuff and I will need to say I am quite impressed.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Nice Post. It’s really a very good article. I noticed all your important points. Thanks.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I cannot thank you more than enough for the blogposts on your website. I know you set a lot of time and energy into these and truly hope you know how deeply I appreciate it. I hope I’ll do a similar thing person sooner or later.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson gen5 купить в спб dn-pylesos-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

где купить дайсон в санкт петербурге pylesos-dn-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

ремонт пылесоса дайсон в спб ремонт пылесоса дайсон в спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

you may have an ideal blog here! would you prefer to make some invite posts on my blog?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

We absolutely love your blog and find the majority of your post’s to be exactly what I’m looking for. Do you offer guest writers to write content to suit your needs? I wouldn’t mind composing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write about here. Again, awesome weblog!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос dyson пылесос dyson .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I dont think I’ve read anything like this before. So good to find somebody with some original thoughts on this subject. cheers for starting this up. This blog is something that is needed on the web, someone with a little originality.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Some truly interesting info , well written and broadly user genial .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I found your blog through google and I must say, this is probably one of the best well prepared articles I have come across in a long time. I have bookmarked your site for more posts.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hi, I just hopped over to your web-site through StumbleUpon. Not somthing I might typically browse, but I liked your views none the less. Thanks for making something worthy of reading through.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос dyson спб pylesos-dn-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

купить дайсон в санкт петербурге pylesos-dn-kupit-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Good day! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I really enjoy reading through your articles. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that cover the same subjects? Thanks a lot!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thanks for another great post. Where else may anybody get that type of info in such an ideal way of writing? I have a presentation next week, and I’m at the search for such information.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон официальный сайт в санкт петербург dn-pylesos-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson v15 спб dn-pylesos-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон санкт петербург pylesos-dn-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить спб pylesos-dn-kupit-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Sprint speed, fastest players and distance covered statistics

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон купить спб оригинал dn-pylesos-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить дайсон пылесос купить .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson пылесос купить pylesos-dn-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson v15 купить спб pylesos-dn-kupit-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесосы дайсон dn-pylesos-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

купить пылесос дайсон в санкт петербурге беспроводной pylesos-dn-kupit-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

официальный магазин дайсон в санкт петербурге pylesos-dn-kupit-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить дайсон пылесос купить .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

폰테크

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

We’re developing some community services to respond to this, and your blog is helpful.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

how to hack slot machines uk, best australian online casinos and free spins

no deposit online pokies canada, or best casino sign up offers uk

my web blog; why was russian roulette invented (Clifford)

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

ремонт пылесоса дайсон в спб pylesos-dn-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

сервис дайсон в спб pylesos-dn-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I’m impressed, I need to say. Really rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both educational and entertaining, and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

hey there and thank you for your info I’ve definitely picked

up something new from right here. I did however expertise a few technical points

using this web site, as I experienced to reload the website lots

of times previous to I could get it to load

properly. I had been wondering if your Web Page hosting is OK?

Not that I am complaining, but sluggish loading instances times will often affect

your placement in google and can damage your high-quality score if ads and marketing with Adwords.

Well I’m adding this RSS to my e-mail and could look out for

much more of your respective exciting content.

Make sure you update this again very soon.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

free casino slots in united kingdom, real slot machines for sale canada and usa

online casino no deposit bonus codes, or canadian poker free online game

Here is my blog post – baccarat strategy wizard Of Odds

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thank you, I have just been searching for information about this topic for ages and yours is the greatest I’ve discovered till now. But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure about the source?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all people you really recognize what you are talking about! Bookmarked. Kindly also seek advice from my web site =). We can have a link alternate contract between us!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Great post, keep up the good work, I hope you don’t mind but I’ve added on my blog roll.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

алкоголь на дом 24 [url=https://www.alcohub10.ru]алкоголь на дом 24[/url] .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Awesome post. It’s so good to see someone taking the time to share this information

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос дайсон беспроводной купить в спб вертикальный пылесос дайсон беспроводной купить в спб вертикальный .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон санкт петербург официальный dn-pylesos-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

сервис дайсон в спб dn-pylesos-kupit-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить dn-pylesos-3.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

сервис дайсон в спб сервис дайсон в спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

agence seo

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

폰테크

폰테크란 휴대폰을 이용해 빠르게 현금을 확보하는 합법적인 자금 조달 방법입니다. 일반적인 소비 목적의 휴대폰 사용과는 달리 통신사와 유통 구조, 매입 시스템을 활용하여 실질적인 자금 확보가 가능한 방식이며, 진행 과정이 간단하고 진입 장벽이 낮다는 장점이 있습니다. 신용 문제로 금융권 이용이 어렵거나 급전이 필요한 상황에서 현실적인 선택지로 고려됩니다.

폰테크의 기본적인 진행 방식은 크게 복잡하지 않습니다. 먼저 통신사를 통해 스마트폰을 정상적으로 개통한 뒤, 해당 단말기를 매입 업체를 통해 처분합니다. 가격은 모델과 시장 시세, 조건에 따라 달라지며, 판매 대금은 현금 또는 계좌이체로 지급됩니다. 이후 발생하는 요금과 할부금은 사용자 책임으로 관리해야 하며, 이 부분에 대한 관리가 매우 중요합니다. 이는 불법 대출과는 다른 구조로, 휴대폰을 하나의 자산처럼 활용하는 방식이라고 볼 수 있습니다.

폰테크는 일반적인 은행 대출과 비교했을 때 뚜렷한 차이가 있습니다. 복잡한 심사나 서류 절차가 거의 없고, 단시간 내 자금 마련이 가능하다는 점이 가장 큰 특징입니다. 금융 이력이 남지 않기 때문에 신용도에 부담을 느끼는 경우에도 접근이 가능합니다. 하지만 통신요금 미납이나 연체가 발생할 경우 신용도에 영향을 줄 수 있으므로 책임 있는 이용이 필수적입니다.

이 방식을 선택하는 배경은 여러 가지입니다. 급전이 필요한 상황이나 금융 이용이 제한된 경우, 자금 흐름이 필요한 상황 등 다양한 상황에서 고려됩니다. 특히 빠른 자금 유동성이 필요한 경우 실질적인 선택지로 평가됩니다.

확보한 현금은 주식이나 코인 투자, 사업 자금, 생활비 등 여러 방식으로 활용될 수 있습니다. 하지만 이러한 자금 운용은 전적으로 개인의 판단과 책임 하에 이루어져야 하며, 투자에는 항상 손실의 가능성이 존재한다는 점을 충분히 인지해야 합니다. 이 방식은 이익을 약속하는 구조가 아니라 자금 확보 목적의 수단이라는 점을 명확히 해야 합니다.

폰테크는 합법적인 구조이지만 주의해야 할 부분도 분명히 존재합니다. 과도한 휴대폰 개통은 통신사 제재의 대상이 될 수 있으며, 상환 계획 없는 이용은 오히려 리스크가 됩니다. 비정상적인 수익을 약속하거나 명의를 요구하는 경우는 주의해야 하며, 절차는 항상 합법적이고 투명하게 진행되어야 합니다.

결론적으로, 폰테크는 휴대폰과 통신 유통 구조를 활용한 합법적인 자금 조달 방법으로, 올바른 정보와 신중한 판단이 전제된다면 단기 자금 확보에 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 무엇보다 사전 정보 확인과 신중한 선택이 가장 중요합니다.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Good points – – it will make a difference with my parents.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить dn-pylesos-kupit-5.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесосы дайсон pylesos-dn-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон где купить в спб дайсон где купить в спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесосы дайсон спб pylesos-dn-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

доставка алкоголя 24 часа доставка алкоголя 24 часа .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон спб официальный магазин dn-pylesos-3.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson пылесос купить спб dn-pylesos-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос дайсон купить пылесос дайсон купить .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон фен купить оригинальный спб dn-pylesos-kupit-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить спб pylesos-dn-10.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон санкт петербург официальный dn-pylesos-kupit-5.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос дайсон спб pylesos-dn-9.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Of course, what a great site and informative posts, I will add backlink – bookmark this site? Regards, Reader

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить pylesos-dn-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Only a smiling visitor here to share the love (:, btw outstanding style and design .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I favored your idea there, I tell you blogs are so helpful sometimes like looking into people’s private life’s and work.At times this world has too much information to grasp. Every new comment wonderful in its own right.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон сервисный центр санкт петербург dn-pylesos-3.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

алкоголь доставка москва 24 алкоголь доставка москва 24 .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесосы dyson dn-pylesos-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson v15 спб pylesos-dn-8.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос dn-pylesos-kupit-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson v15 спб pylesos-dn-10.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Its wonderful as your other blog posts : D, regards for putting up.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон официальный сайт спб дайсон официальный сайт спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson пылесос спб pylesos-dn-9.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Developing a framework is important.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hey! awesome blog! I happen to be a daily visitor to your site (somewhat more like addict 😛 ) of this website. Just wanted to say I appreciate your blogs and am looking forward for more!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

A friend of mine advised this site. And yes. it has some useful pieces of info and I enjoyed scaning it. Therefore i would love to drop you a quick note to express my thank. Take care

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson пылесос беспроводной купить спб pylesos-dn-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

A friend of mine advised me to review this site. And yes. it has some useful pieces of info and I enjoyed reading it.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесосы дайсон pylesos-dn-6.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Pretty impressive article. I just stumbled upon your site and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your opinions. Any way I’ll be coming back and I hope you post again soon.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hello. Great job. I did not expect this on a Wednesday. This is a great story. Thanks!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Is it okay to put a portion of this on my weblog if perhaps I post a reference point to this web page?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

купить пылесос дайсон в санкт dn-pylesos-3.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон купить спб дайсон купить спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson v15 купить спб dn-pylesos-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

сервис дайсон в спб dn-pylesos-kupit-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

dyson gen5 купить в спб pylesos-dn-8.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

сервис дайсон в спб сервис дайсон в спб .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

If wings are your thing, Tinker Bell’s sexy Halloween costume design is all grown up.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

заказать алкоголь 24 часа заказать алкоголь 24 часа .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон санкт петербург дайсон санкт петербург .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I would share your post with my sis.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

магазин дайсон в спб dn-pylesos-3.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос беспроводной купить спб pylesos-dn-7.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

купить пылесос дайсон спб dn-pylesos-2.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон пылесос купить спб pylesos-dn-10.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон сервисный центр санкт петербург dn-pylesos-kupit-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

дайсон санкт петербург dn-pylesos-4.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос dyson купить dn-pylesos-kupit-5.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесос dyson пылесос dyson .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

ночная доставка алкоголя ночная доставка алкоголя .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

пылесосы dyson спб pylesos-dn-9.ru .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

slot gacor situs toto situs toto 4d

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thanks for your patience and sorry for the inconvenience!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye -.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

buy poker machine united kingdom, united statesn roulette rules usa and crusader lvl 1 gambling, or

who Owns the ocean casino in ac top online pokies

and casinos in australia day

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

top sportwetten anbieter

Also visit my web page – Wetten Dass gewinner

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

spiusailla no deposit bonus code, no deposit bonus on sign up

usa and casino gananoque ontario canada, or united statesn online casino minimum

deposit $10

Feel free to surf to my blog post: vicksburg ms gambling

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hey very cool site!! Man .. Beautiful .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your website and take the feeds also…I’m happy to find so many useful information here in the post, we need develop more strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

australian online casinos that accept paypal, bet365 new zealandn roulette instructions and interactive gambling canada, or minimum dollar 5 deposit how Many syllables does casino australia

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I favored your idea there, I tell you blogs are so helpful sometimes like looking into people’s private life’s and work.At times this world has too much information to grasp. Every new comment wonderful in its own right.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

It’s clear you’re passionate about the issues.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thank you for all the information was very accurate, just wondering if all this is possible.~

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

What made you first develop an interest in this topic?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I don’t normally comment on blogs.. But nice post! I just bookmarked your site

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

There is perceptibly a lot to identify about this. I consider you made some good points in features also.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Buy Psychedelics Online

TRIPPY 420 ROOM is presented as a full-service psychedelics dispensary online, with a focus on carefully prepared, high-quality medical products across several product categories.

Before purchasing psychedelic, cannabis, stimulant, dissociative, or opioid products online, users are provided with a clear service structure that outlines product availability, shipping options, and customer support. The store features more than 200 products across multiple formats.

Delivery pricing is determined by package size and destination, and includes both regular and express shipping. Each order includes access to a hassle-free returns system and a strong focus on privacy and security. Guaranteed stealth delivery worldwide is a core element, with no added fees. All orders are fully guaranteed to support reliable delivery.

The catalog spans cannabis flowers, magic mushrooms, psychedelic products, opioid medications, disposable vapes, tinctures, pre-rolls, and concentrates. All products are shown with transparent pricing, and visible price ranges for products with multiple options. Additional informational content is included, with references including “How to Dissolve LSD Gel Tabs”, along with direct options to buy LSD gel tabs and buy psychedelics online.

The business indicates its office location as United States, CA, and provides multiple contact channels, such as phone, WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and email. The service highlights 24/7 express psychedelic delivery, placing focus on accessibility, discretion, and consistent support.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

medidor de vibraciones 2

https://vibromera.es/medidor-de-vibraciones-2/

Dispositivos de equilibrado: clave para el desempeno optimo y estable de las maquinas

En el mundo de la tecnologia moderna, donde la optimizacion y la fiabilidad del equipo son de relevancia critica, los sistemas de equilibrado desempenan un funcion esencial. Estos herramientas avanzadas estan destinados a equilibrar y estabilizar partes rotativas, ya sea en maquinaria industrial, automoviles y camiones o incluso en electrodomesticos.

Para los tecnicos de servicio y los expertos en ingenieria, trabajar con tecnologias de equilibrado es clave para asegurar el trabajo seguro y continuo de cualquier mecanismo giratorio. Gracias a estas soluciones tecnologicas avanzadas, es posible minimizar de forma efectiva las oscilaciones, el ruido y la carga sobre los cojinetes, prolongando la vida util de piezas de alto valor.

Igualmente crucial es el papel que ejercen los equipos de balanceo en la atencion al cliente. El soporte tecnico y el mantenimiento regular utilizando estos sistemas garantizan servicios de alta calidad, mejorando la experiencia del usuario.

Para los propietarios, la implementacion en equipos de calibracion y sensores puede ser decisiva para elevar la eficiencia y productividad de sus equipos. Esto es especialmente relevante para los administradores de negocios medianos, donde toda mejora es significativa.

Ademas, los equipos de balanceo tienen una amplia aplicacion en el campo de la seguridad y el control de calidad. Ayudan a prever problemas, ahorrando gastos elevados y fallos mecanicos. Mas aun, los informes generados de estos sistemas pueden utilizarse para optimizar procesos.

Las industrias objetivo de los equipos de balanceo cubren un amplio espectro, desde la industria ciclista hasta el control del medioambiente. No importa si se trata de fabricas de gran escala o negocios familiares, los equipos de balanceo son necesarios para asegurar un funcionamiento eficiente y sin interrupciones.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

spieler gegen spieler wette

Check out my web blog: englische wettanbieter

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Wow, that’s what I was exploring for, what a material! present here at this web

site, thanks admin of this site.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I will right away take hold of your rss feed as I can not to find your e-mail subscription link or e-newsletter service.

Do you’ve any? Kindly permit me realize so that I could subscribe.

Thanks.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

These are some of the most important issues we’ll face over the next few decades.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

PSYCHEDELICS DISPENSARY

TRIPPY 420 ROOM is presented as a full-service psychedelics dispensary online, with a focus on carefully prepared, high-quality medical products across multiple categories.

Before placing an order for psychedelic, cannabis, stimulant, dissociative, or opioid products online, users are provided with a clear service structure covering product availability, delivery options, and support. The store features more than 200 products across multiple formats.

Delivery pricing is determined by package size and destination, offering both regular and express delivery options. Orders are supported by a hassle-free returns process and a strong focus on privacy and security. The service highlights guaranteed worldwide stealth delivery, without additional charges. Every order is fully guaranteed to support reliable delivery.

The product range includes cannabis flowers, magic mushrooms, psychedelic products, opioid medication, disposable vapes, tinctures, pre-rolls, and concentrates. All products are shown with transparent pricing, including defined price ranges where multiple variants are available. Additional informational content is included, including references such as “How to Dissolve LSD Gel Tabs”, as well as direct options to buy LSD gel tabs and buy psychedelics online.

The dispensary lists its operation in the United States, California, and offers multiple communication channels, including phone, WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and email. A 24/7 express psychedelic delivery service is emphasized, framing the service around accessibility, privacy, and ongoing customer support.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I wrote down your blog in my bookmark. I hope that it somehow did not fall and continues to be a great place for reading texts.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

While this issue can vexed most people, my thought is that there has to be a middle or common ground that we all can find. I do value that you’ve added pertinent and sound commentary here though. Thank you!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

of course like your web-site however you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to tell the reality then again I will surely come back again.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Some truly interesting info , well written and broadly user genial .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

When are you going to post again? You really entertain me!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Our local network of agencies has found your research so helpful.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

We can see that we need to develop policies to deal with this trend.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Took me time to read the material, but I truly loved the article. It turned out to be very useful to me.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

späte tore wetten

my page: online sportwetten Beste quoten

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

sportwetten online österreich

My homepage; wettbüro mainz

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

was ist ein buchmacher

Also visit my blog: basketball Wetten quoten

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Apuestas copa Libertadores de deportes online

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

betsson sportwetten bonus

Feel free to visit my website :: wett Tipps heute net

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I am glad to be one of the visitors on this great site (:, appreciate it for putting up.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Good day! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I really enjoy reading through your articles. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that cover the same subjects? Thanks a lot!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

폰테크

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

The start of a fast-growing trend?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

trucos para ganar en pronostico apuestas la liga (Lida) de futbol

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I think it is a nice point of view. I most often meet people who rather say what they suppose others want to hear. Good and well written! I will come back to your site for sure!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

TUK TUK RACING KENYA

Round 5 is here — and everything escalated fast.

This is TUK-TUK RACING KENYA, where talent and street experience clash.

This time, drivers face a brutal new round:

• narrow turns and water hazards

• visual chaos and surprise obstacles

• envelopes with cash on the line

• and a relentless TUK-TUK TUG OF WAR finale — where power and grip matter more than speed

Colors fly, places change in an instant, and nothing is decided until the end.

A single error means elimination. One solid move takes you forward.

This is not scripted.

You can’t predict what happens next.

This is Kenya’s Tuk-Tuk Showdown — Round 5.

Watch till the end and tell us:

Who dominated this round?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

kenya viral racing

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

폰테크

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

A cool post there mate ! Thank you for posting.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

como se tributan las trucos apuestas deportivas (https://www.medicalmarijuanabarcelona.com/apuestas-digitales-psg-barca/) deportivas

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bonos apuestas deportivas (Rene) para champions

league

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Unquestionably believe that which you said. Your favorite reason seemed to be on the net the easiest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed while people consider worries that they plainly don’t know about. You managed to hit the nail on the head. Will probably be back to get more. Thanks

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I appreciate, cause I found just what I was looking for. You’ve ended my four day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day. Bye -.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I do not know who you are but certainly you are going to a famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Most often since i look for a blog Document realize that the vast majority of blog pages happen to be amateurish. Not so,We can honestly claim for which you writen is definitely great and then your webpage rock solid.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I just couldn’t leave your website before suggesting that I really enjoyed the usual information an individual supply on your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to investigate cross-check new posts

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Το στοίχημα αποτελεί αναπόσπαστο κομμάτι της ψυχαγωγίας για πολλούς Έλληνες παίκτες. Καθώς η εγχώρια αγορά υπόκειται σε αυστηρή ρύθμιση και περιορισμούς, ένα μεγάλο μέρος των παικτών στρέφεται προς ξένες στοιχηματικές εταιρείες που προσφέρουν μεγαλύτερη ευελιξία, καλύτερες αποδόσεις, περισσότερες επιλογές και καινοτόμα χαρακτηριστικά. Ειδικά για όσους αναζητούν μια πιο πλούσια στοιχηματική εμπειρία, οι πλατφόρμες του εξωτερικού προσφέρουν σημαντικά πλεονεκτήματα. Ο όρος ξένες στοιχηματικές εταιρείες που δέχονται Έλληνες δεν αφορά απαραίτητα αδειοδοτημένους παρόχους στην Ελλάδα, αλλά ιστοσελίδες που λειτουργούν νόμιμα υπό διεθνείς άδειες όπως της Κουρασάο, της Ανζουάν ή της Κόστα Ρίκα και επιτρέπουν εγγραφή και στοιχηματισμό από Έλληνες χρήστες. Το ενδιαφέρον για τέτοιου είδους εταιρείες αυξάνεται συνεχώς, καθώς προσφέρουν όχι μόνο καλύτερα μπόνους και προωθητικές ενέργειες, αλλά και υποστήριξη σε κρυπτονομίσματα, μηδενική γραφειοκρατία και πιο φιλικές προς τον χρήστη εμπειρίες.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

I was reading through some of your content on this internet site and I believe this web site is very informative ! Continue posting .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Good post. I study something more difficult on different blogs everyday. It’s going to always be stimulating to learn content material from other writers and observe a little bit one thing from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content material on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link in your web blog. Thanks for sharing.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

My brother suggested I might like this websiteHe was once totally rightThis post truly made my dayYou can not imagine simply how a lot time I had spent for this information! Thanks!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

폰테크

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

it is a really nice point of view. I usually meet people who rather say what they suppose others want to hear. Good and well written! I will come back to your site for sure!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

bonjour I love Your Blog can not say I come here often but im liking what i c so far….

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Clear, concise and easy to access.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

OK, you outline what is a big issue. But, can’t we develop more answers in the private sector?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Surprisingly good post. I really found your primary webpage and additionally wanted to suggest that have essentially enjoyed searching your website blog posts. Whatever the case I’ll always be subscribing to your entire supply and I hope you jot down ever again soon!

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

gamble online slots

Gates of Olympus — популярный слот от Pragmatic Play с принципом Pay Anywhere, цепочками каскадов и коэффициентами до ?500. Действие происходит у врат Олимпа, где Зевс активирует множители и превращает каждое вращение случайным.

Сетка слота выполнено в формате 6?5, а комбинация формируется при появлении 8 и более совпадающих символов без привязки к линиям. После выплаты символы пропадают, их заменяют новые элементы, активируя каскады, дающие возможность получить серию выигрышей за один спин. Слот считается игрой с высокой волатильностью, поэтому не всегда даёт выплаты, но в благоприятные моменты способен порадовать крупными выплатами до 5000 ставок.

Чтобы разобраться в слоте доступен демо-версия без финансового риска. Для ставок на деньги стоит использовать официальные казино, например MELBET (18+), учитывая заявленный RTP ~96,5% и правила выбранного казино.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

онлайн казино игры слот Gates of Olympus —

Gates of Olympus slot — популярный онлайн-слот от Pragmatic Play с системой Pay Anywhere, цепочками каскадов и коэффициентами до ?500. Действие происходит на Олимпе, где Зевс активирует множители и превращает каждое вращение непредсказуемым.

Игровое поле представлено в виде 6?5, а выплата засчитывается при сборе 8 и более совпадающих символов в любой позиции. После расчёта комбинации символы пропадают, их заменяют новые элементы, запуская каскады, способные принести несколько выплат в рамках одного вращения. Слот является игрой с высокой волатильностью, поэтому способен долго молчать, но при удачных раскладах способен порадовать крупными выплатами до 5000 ставок.

Для тестирования игры доступен бесплатный режим без вложений. Для ставок на деньги целесообразно использовать официальные казино, например MELBET (18+), принимая во внимание заявленный RTP ~96,5% и правила выбранного казино.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hi, possibly i’m being a little off topic here, but I was browsing your site and it looks stimulating. I’m writing a blog and trying to make it look neat, but everytime I touch it I mess something up. Did you design the blog yourself?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Some truly interesting info , well written and broadly user genial .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

play online slots games Gates of Olympus —

Слот Gates of Olympus — известный игровой автомат от Pragmatic Play с механикой Pay Anywhere, каскадными выигрышами и коэффициентами до ?500. Действие происходит у врат Олимпа, где бог грома повышает выплаты и делает каждый спин непредсказуемым.

Сетка слота имеет формат 6?5, а выплата начисляется при сборе 8 и более идентичных символов в любом месте экрана. После расчёта комбинации символы пропадают, на их место опускаются новые элементы, запуская серии каскадных выигрышей, которые могут дать несколько выплат в рамках одного вращения. Слот относится игрой с высокой волатильностью, поэтому не всегда даёт выплаты, но при удачных каскадах даёт крупные заносы до 5000 ставок.

Для тестирования игры доступен демо-версия без вложений. Для ставок на деньги целесообразно использовать лицензированные казино, например MELBET (18+), учитывая RTP около 96,5% и условия площадки.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Developing a framework is important.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Equili

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

гейтс оф олимпус

Gates of Olympus — хитовый онлайн-слот от Pragmatic Play с механикой Pay Anywhere, каскадами и усилителями выигрыша до ?500. Сюжет разворачивается у врат Олимпа, где Зевс усиливает выигрыши и делает каждый раунд случайным.

Сетка слота имеет формат 6?5, а комбинация засчитывается при сборе 8 и более идентичных символов без привязки к линиям. После формирования выигрыша символы удаляются, сверху падают новые элементы, формируя цепочки каскадов, дающие возможность получить несколько выплат за одно вращение. Слот считается игрой с высокой волатильностью, поэтому может долго раскачиваться, но при удачных раскладах даёт крупные заносы до 5000 ставок.

Для тестирования игры доступен демо-режим без финансового риска. Для ставок на деньги стоит использовать официальные казино, например MELBET (18+), учитывая RTP около 96,5% и правила выбранного казино.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Is it okay to put a portion of this on my weblog if perhaps I post a reference point to this web page?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Hi my family member! I want to say that this article is amazing, great written and include approximately all important infos. I’d like to see more posts like this .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Some truly interesting info , well written and broadly user genial .

Your comment is awaiting moderation.