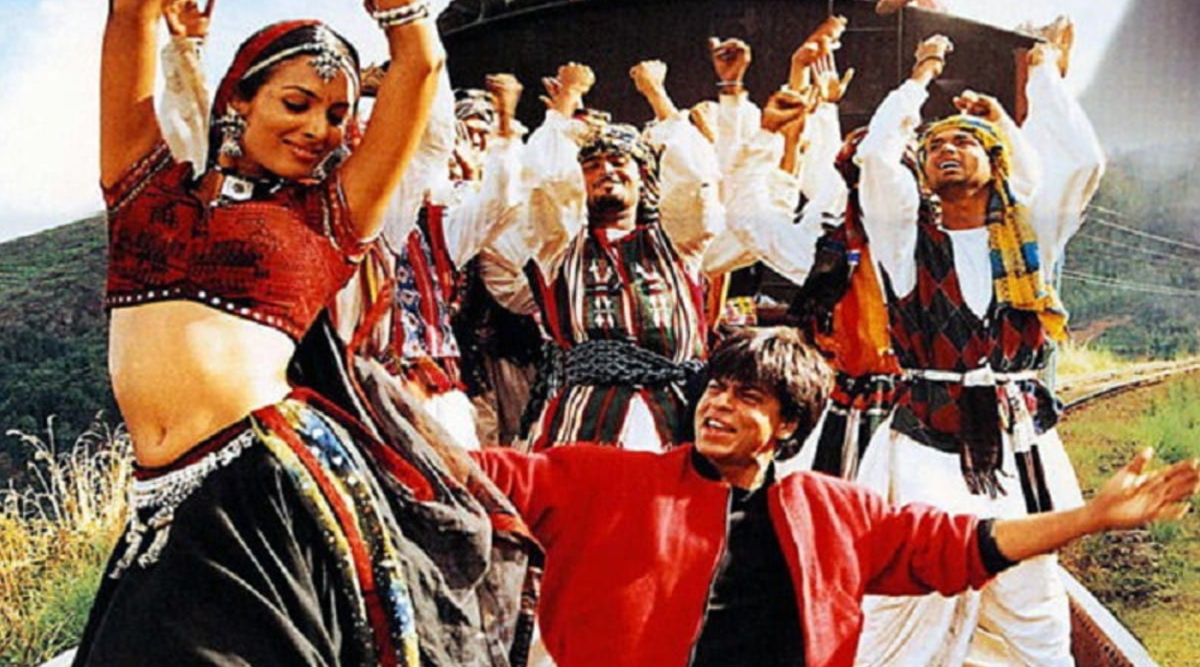

Chaiyan chaiyan is engraved as a core memory. At four years old when Abbagot me a tiny toy flip phone, playing upbeat Bollywood songs, I truly believed I had arrived. I, distinctly, remember that when you pressed number 4, you could hear Sukhwinder Singh & Sapna Awasthi’s melodious voices chiming “Chaiyan chaiyan”. That song was replayed to the point it settled as a default setting. I threw my hands in the air and danced as did every other kid my age.

There was something powerful about the song, and the way it became a cultural catalyst prompting everybody to let go and move.

Chaiyan chaiyan was a bop, but not one which consisted merely of mindless lyrics and catchy beats. The lyrics, composed by Gulzar still stand relevant to modern Sufi poetry; filled to the brim with Sufi metaphors, reflecting the shared spiritual history of South Asia.

وہ یار ہے جو خوشبو کی طرح

جس کی زباں اردو کی طرح

گل پوش کبھی اترائے کہیں

مہکے تو نظر آجائے کہیں

تعویز بنا کے پہنوں اسے

آیت کی طرح مل جائے کہیں

A case study of Chaiyan chaiyan and Dhoom’s skyward popularity in Pakistan in the early 2000s reaffirms Bollywood’s role in shaping the contemporary pop culture of Pakistan. All of us have grown up listening to Bollywood hits. So much that they have constituted a permanent spot in our consciousness.

The tenuous political relationship between Pakistan and India, the militarised narrative builders, the hyper-religious strata of society and the self-proclaimed custodians of culture and religion on both sides of the border continue to fuel the fire of a rivalry which since its criminal inception should have been permitted to burn out.

On the 22nd of February, Dawn Images published an article titled “Pakistan is (finally) getting over its Bollywood mania’ which debated that the ‘wave of Bollywood mania’ is finally over and we are finally celebrating new, home-grown content instead.”

The conclusive statement and tone of the article do not sit right considering that it came out in the same week when LUMS celebrated its Bollywood Day. The batch of 2023, in the wake of their graduation week, decided to dress up as their favourite Bollywood characters, ranging from Devdas, Jhilmil Chatterjee, and Barfi to Baburao from Hera Pheri.

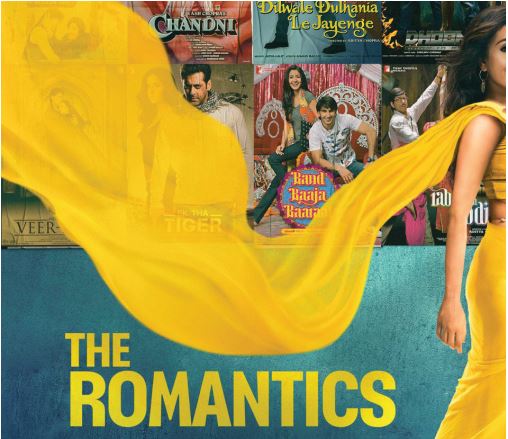

The same week, Netflix’s production The Romantics aired. It featured archival footage and celebrity interviews, this docuseries celebrates the life and thriving legacy of the late Bollywood filmmaker Yash Chopra.

Pakistani Twitter revels in Bollywood content. 6 out of 7 days a week, a Bollywood movie sits firmly at the number one spot in the ‘Trending Now’ list on Netflix.

Considering the aforementioned context and then stating that Pakistan is over its Bollywood mania, not only seems oblivious to the cultural reality of the country, but it also seems to be perpetuating Bollywood as the ‘other’s’ narrative.Seeped in nostalgia, the Bollywood Day at LUMS was representative of a generation that grew up consuming Bollywood content through camera print DVDs, pirated torrent sites and other illegal means when Pakistan banned the screening of Bollywood films.

The constant usage of words ‘culture’ and ‘religion’ interchangeably is a common misconception that results in a paranoia of cultural invasion. The paranoia seldom bothers anyone when it is the consumption of Korean or Turkish content like Ertugral, Ishq-e-Mamnu and, Elif that takes the nation by storm. Not even when it is made normalised and endorsed by the Prime Minister himself.

However, when it comes to Bollywood, the paranoia translates into an immediate ban. The ban on the screening of Bollywood films in Pakistan is not a recent phenomenon, it has a long and complicated history that dates back to the early days of the two countries’ independence. There are many factors behind the ban of Bollywood films, most of them related to the suspicion of ‘cultural invasion’ which is irrational considering centuries of shared history and culture rooted within the collective consciousness of the region.

The shared lore, characters and prevalent tropes have seeped deep into our consciousness, despite the militant effort to create a divide between the two countries.

Over the years, the ban on Indian films has been implemented and lifted several times, depending on the political and social climate of the two countries. In the 1970s, the Pakistani government imposed a ban on Indian films in an attempt to promote the country’s film industry. However, the ban was lifted in the 1980s, when Pakistani filmmakers were struggling to compete with the high-quality and well-funded Indian film industry. The ban was reimposed in 2008, following the Mumbai attacks, which were carried out by terrorists believed to have links to Pakistan.

The Indian film industry has often been viewed as a soft target and a way for Pakistan to retaliate against India. The ban was lifted again in 2012 but was once again imposed in 2016 after tensions between the two countries escalated due to a series of cross-border incidents. The ban has been controversial, with some arguing that it harms the Pakistani film industry, which struggles to compete with the more established Indian film industry.Others argue that it is a matter of national pride and that Pakistani audiences should support their film industry instead of relying on Indian films.

Despite the multiple bans, Pakistanis’ love for healthy brown representation transcends the state-level xenophobic agenda. The popularity of Bollywood in Pakistan can be pinned down to a myriad of reasons. To name a few, it is due to cultural affinity, emotional resonance, accessibility, spectacle and linguistic familiarity. The two countries share a common cultural heritage, which includes language, music, dance, and films. This cultural similarity has created an affinity between the two nations, and Pakistani audiences find it easy to relate to Indian films, their characters and the aesthetics shown on the screen.

Carrying international popularity, Bollywood has also become a cultural currency for all South Asian diasporic communities. No amount of state propaganda, bans, and narrow-visioned articles can deny thechokehold Bollywood has over the pop culture representation of South Asia.

Pitting one art industry against the other challenges the universality of creative expression. Art is borderless. It is a universal language that transcends borders and speaks to the hearts and minds of people from all walks of life. It has the power to connect and erase whatever minimal differences we have and it should be allowed to do so, free of bans, prejudice and misleading articles.

The writer is our Editorial Assistant and an oral historian.