Pakistan has announced one-year extension in the registration cards of the Afghan refugees, thereby putting off its earlier decision to repatriate Afghan refugees living in Pakistan. The decision, endorsed by the federal cabinet, was announced on 10 July, less than a week after Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s meeting with the visiting head of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), Filippo Grandi.

The decision is apparently a result of the widespread criticism sparked both inside Pakistan as well as on a global level following Pakistan’s announcement of enforced deportations of Afghan refugees on 3 October, 2023. On that day, the government announced a directive to all Afghan refugees, both registered and unregistered, to voluntarily leave Pakistan by 31 October, failing which they would be forcibly deported.

The humanitarian issues which it triggered soon after the policy announcement, and the brutal handling of refugee communities when the 1 November 2023 deadline for voluntary repatriations passed, attracted widespread criticism of the policy.

More significantly, the policy was announced and implemented by a caretaker government which did not have any legal or constitutional mandate to indulge in such decisions, triggering perceptions that Pakistan was using refugees as a football in its troubled relations with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

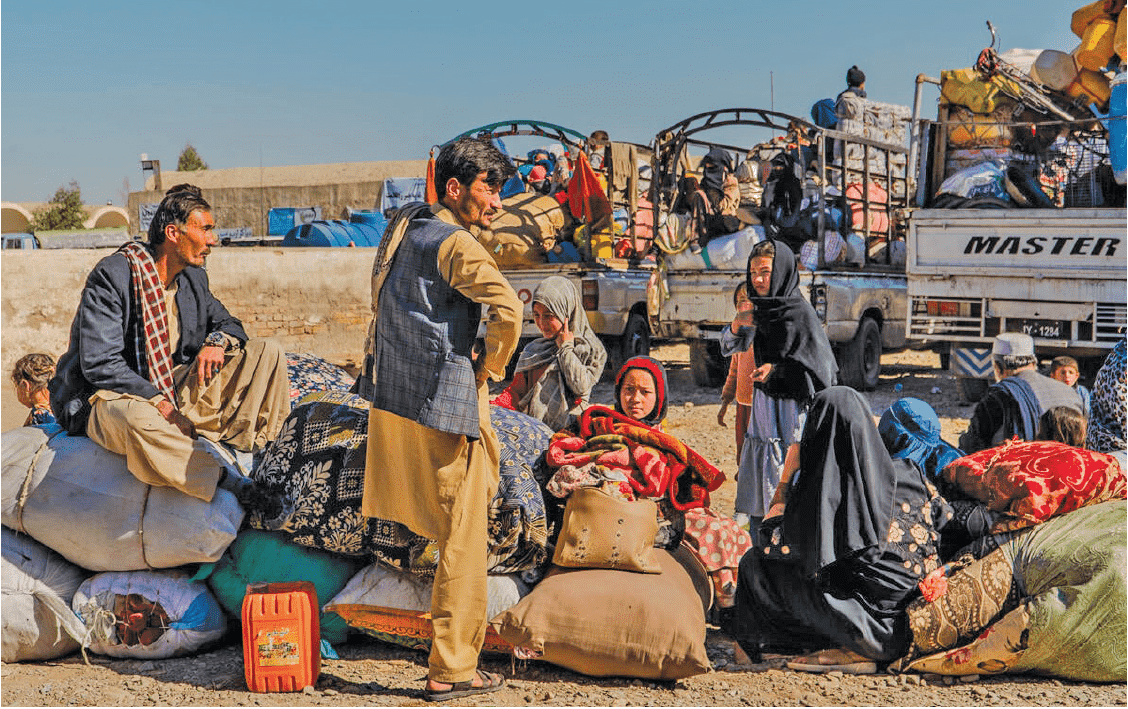

Pakistan has been hosting millions of Afghan refugees since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. The latest influx started in August 2021 when the Taliban regained power in Afghanistan, prompting some 600,000 to 800,000 Afghans to seek refuge in neighbouring Pakistan.

According to the government, Pakistan currently hosts nearly three million Afghans, with close to 2.4 million possessing some form of legal documentation. Of these, almost 1.5 million hold a UNHCR Proof of Residence (PoR) card, and another 800,000 possess an Afghan Citizenship Card (ACC).

How it started

It was a hurriedly drawn plan, under which the concerned government departments started a mapping exercise to update district-wise data of Afghan refugees. Personnel of some military intelligence units were also involved in this exercise.

At the same time, the government started setting up control rooms in all the areas where refugee population had a presence, and set up transit points where the arrested refugees would be brought and then transported to the border.

According to officials contacted by The Wayward, the exercise was started on an emergency basis and there was no long-term planning to give to the refugees enough time to wind up their lives in a country where most of them had been born, and to prepare for life in a country they had never seen, and where basic human rights were non-existent.

Also, the sudden decision caught the concerned government departments in a state of ill-preparedness, and what followed was gross administrative incompetence, widespread corruption and massive human rights violations.

The situation was the worst in Sindh, and also to an extent in Punjab, where the refugees suffered the harshest treatment. Here, the authorities did not wait until the 31 October deadline for voluntary repatriation, and started a brutal crackdown in which refugees doing labour jobs, collecting garbage or running roadside food stalls started to disappear from the streets.

This happened at a time when a large number of refugees in Sindh had already been facing arrests, jails and court trials under the Foreigners Act. Local observers say that such actions by the Sindh police had started since mid-2022, and increased manifold after the 3 October deportation plan was announced.

Police corruption was a main trigger for such brutalities, according to observers. There were cases in which even registered refugees were arrested, their ID cards snatched or destroyed, and then released after paying bribes.

Those harassed by the authorities before the 3 October announcement and unable to pay them bribes were mostly taken to the courts under the Foreigners’ Act. But this legal procedure ended following the 3 October announcement, and those picked up by the police had either to pay them bribes, or face deportation.

Witnesses interviewed by The Wayward described how police would raid refugee homes during midnight hours, wake up and arrest men, women and children, and take them away to deportation centres, leaving their homes and hearths behind.

There was also the issue of racial profiling, particularly in Sindh and Punjab, where many Pakistani nationals were also arrested and sent for deportation. This happened mainly because the officials conducting such raids did not have the socio-cultural and linguistic awareness about the communities they were operating in, and could not tell the difference between Afghans and the Pakistani Pashtoons.

As the operation intensified, many refugees went into hiding to avoid arrest and deportation until they had sold off their assets here. But the potential buyers, knowing the predicament which the seller faced, offered them very small prices for those assets. In many cases, departing refugee families left their unsold electronic gadgets on the roadsides in Karachi’s Sohrab Goth area when they were picked up and taken to transit points by the police.

Human sufferings

Interviews of witnesses at the deportation points in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan provinces reveal a number of childbirths that refugee women suffered during their deportation. In many cases, the newborn kids did not survive. In most cases, however, the local communities offered support to pregnant women, offering them residence and care in their homes during the childbirth and the subsequent period of recovery.

Dozens of child deaths due to exposure to cold weather were also reported from both these regions. Some older people also died during the deportation. Some bodies were taken across the border by their relatives, while others, mostly children, were buried in graveyards on the Pakistani side of the border.

And there were family separations, mainly involving children, mostly in Sindh province. This happened when the police, unable to track down a family that might have gone into hiding, picked up their children from streets and sent them for deportation. In a couple of such cases, Pakistani children were also deported. But thanks to the smart-phone age, many such families were able to reunite as the separated members were able to contact their families at one point or another during the deportation process, and were then helped by human rights activists operating in the field to reunite on both sides of the border.

Those deported also included vulnerable Afghan individuals, such as those who had worked with Afghan forces or foreign NGOs, etc, during the pre-Taliban era and were a potential target of the Taliban. These people also included a number of Christian converts, who could now face death sentence in Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s motives

The general narrative being promoted by Pakistan to justify its decision was that Afghans were a burden on Pakistani economy, and were promoting terrorism in Pakistan.

But many analysts believe the real motive behind this move is to perpetuate Pakistan’s colonial heritage. In other words, Pakistan is being ruled by colonial institutions, dominated by the military establishment. And its basic source of income is to serve the interests of the Western powers in a region where Russian and Chinese influence is once again on the rise.

According to these analysts, the main thought behind such strategies is to carve out niches in a weakened Afghanistan and thereby make roads across it, and into the Central Asian region with a view to help the Western powers curb the spread of influence of these countries in this region. Pakistan has done this before, and is likely to continue with such strategies in the future. Afghans, and people of its adjacent regions in KP and Balochistan are used as a fuel to ignite such fires, these analysts say.

The writer is a senior journalist and former correspondent BBC.