Some environmental disasters get noticed by Sindh’s political activists while others get swept under the rug. The federal government announced plans for six canals on the Indus River to provide water to Cholistan in South Punjab. Multiple left-wing and mainstream political parties registered their protests that this would negatively impact water scarcity and agriculture in Sindh. But what is missing from this debate is that this disaster is not unique, and one of a series of ecocide events are plaguing Sindh’s natural landscape and agricultural productivity. Sindhu Darya’s destruction, is from within and by its own in consort with global and local capitalists. The project of colonisng Sindh – extraction, mining, erasure of farms and pastures for the infrastructure-industrial complex is at full throttle.

Hence, the story of Indus has to be told within a capitalist-extractivist framework. The issue should not be reduced to parochialism and false demonisation of Punjab or Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa to promote certain elite power groups over others – but as peasants against systemic dispossession.

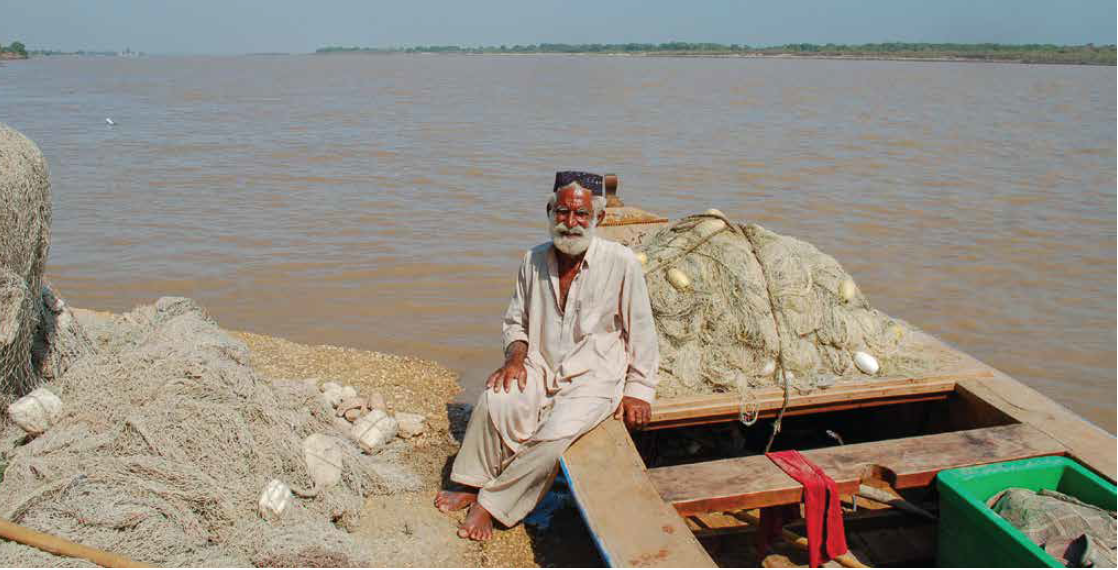

Organisations like the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum have documented the Indus delta as a disaster zone and it is abundantly evident that more canals on the Indus will further destroy the deltaic region. The Indus Water Treaty of 1991 between the provinces was scientifically flawed and politically difficult to implement and failed to flush sufficient streams south of Kotri Barrage and restore Indus. In the last three decades, sea water intruded deltaic creeks and devastated the growth of mangroves, once lush nurseries of marine life, the Indus Delta hailed as a rich agricultural area is now reduced to a place where drinking water is no longer available and farming and fishing communities have faced involuntary displacement.

The whole story of the Indus River would be told quite differently if it wasn’t to fuel a distracting inter-provincial rift – to unite South Punjab and Sindh farmers to support their depleting livelihoods associated with the Indus. It has to be told in conjunction with the destruction of all water systems of Sindh by all and sundry. The Government of Sindh (GoS) allowed the Malir River in Karachi to be occupied to protect elite residential investments on the M-9 and to connect the city to these. Its banks are now cut open to accommodate the 39-kilometer Malir Expressway. GoS has with impunity permitted Malir River and its tributaries at Kirthar National park to be mercilessly mined for sand and gravel. This has irreversibly damaged their aquifers and capacity to support wildlife – and its adjoining mountain ranges are being illegally cut for rock. Manchar Jheel, a hub for local and migratory birds, turned toxic after a badly designed drain from the Indus, the Right Bank Outfall Drain (RBOD), dumped agricultural effluents in it.

Gadap farmers are aghast that leases for orchards and farms they enjoyed for over forty years are not being renewed since 2021 as the GoS eyes all land in Karachi’s outskirts for dystopian urbanisation. Karoonjhar, an ancient mountain range, is being blown up for its minerals destroying its water systems that had given Nagarparkar farmers reprieve for vegetable and fruit cultivation. In 2013, Badin farmers complained influential local landlords were siphoning off water that led to desertification of 66,750 acres of agricultural land.

The ill-fated Right Bank Outfall Drain was partially fund by the Asian Development Bank. The World Bank funded the equally ill-fated Left Bank Outfall Drain of the Indus, made without consulting indigenous peoples and local peasants.

Banks are embedded in an economy that is agnostic to peoples’ cultures, spiritual values, and traditional livelihood systems. They come when it is financially beneficial for them, and disappear when it is politically inexpedient. An example is the World Bank facilitated Indus Water Treaty of 1960 between India and Pakistan – whatever fanfare led to it then, today their role appears politically lethargic, limited to appointing a neutral arbitrator in case of a dispute. This is worrisome as these banks are now producing ideologically neo-liberal ‘knowledge repositories’ on just transition from coal – but when the ecological ruin from coal becomes widespread, they may not offer tangible solutions or be held accountable in any jurisdiction.

While international financial institutions pay lip service to sovereignty, they do not think twice usurping sovereignty by ‘gently’ coercing weak states to set standards for social legitimacy for their lending projects. Bank environmental and social rules and accountability mechanisms become templates to facilitate the funding process. It does not matter that states already had local rules; they are revamped to minimise lender-liability and to give the semblance of compliance with human rights principles.

While banks can cause weak nations to subvert their legislative autonomy, their own jurisdictional gateways to people’s interests are tightly sealed. The World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes granted a powerful Transnational Corporations (TNCs), Tethyan Copper Company, rights to mine in Balochistan, but had no room for local Baloch to intervene to present their case of indigenous rights.

Neo-liberal colonisation follows the same techniques of their predecessor forms of dispossession. In Empires of the Indus, Albinia described how Alexander Burnes surveyed the River Indus in 1830s to enable conquest and profiteering. Banks and TNCs similarly do their research as groundwork for lending; in 2012, the Japan International Cooperation Agency conjured up a transportation blueprint for Karachi and in 2018, the World Bank pontificated on how Karachi may become more livable. But none of these reports mention the debt trap or the role of carbon majors operating in Sindh in pollution, poverty, and malnutrition. While the colonial apparatus orchestrated policing, surveillance, and false criminalisation of peasants, the new extraction model relies exclusively on brown-skinned compradors to lead the repressive work.

The story of the Indus cannot be told unless we address the mechanisms of erasure that have led to selective activism and incomplete discourse – insufficient reporting from rural areas, lack of effective accountability for business human rights violations at the United Nations at local level, rolling back of people centered laws from the 70s to the early 2000s, a deficit of judicial intellect and autonomy, and since 2015 a shrinking space for civil society. That the GoS did not even register the 2024 flood or mobilise disaster apparatus is an indictment against journalism. The space for NGOs was already compromised as foreign donors imposed human rights agendas where gendered violence and restrictions on free speech were seen as attacks on autonomous rights possessing individuals as opposed to being rooted in an anti-poor political economy. The band-aid NGO work and the trickle of knowledge they produce, got circumscribed by new rules that limited their operations. Local courts are caught between the impetus to write decisions using contemporary climate justice language and cognisance of how their judgments may not be practically enforced. Laws that regularised villages, that provided a framework for environmental review, that defended forests from trespassing, are being ignored and other ameliorative legal regimes are being gradually dismantled.

It is no other than the departments of the GoS doing this with milbas with TNCS also negotiating for space. Arguments of demographic change, ethnic shifts, and provincialism may incite people into activism for the Indus in the short run but in the long run this paralyses resistance as it misses the real but elusive target – the international capitalist economy.

The writer is a lawyer, political activist, and teaches at IBA, Karachi.