As the sun climbed above the jagged mountains of Balochistan on March 11, the rhythmic chug of the Jaffar Express echoed through the historic tunnels of Bolan Pass. What began as a routine journey soon descended into a nightmare that would grip the nation for over 30 hours.

In one of the most audacious and brutal attacks in Pakistan’s recent memory, separatist militants from the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) hijacked the Jaffar Express mid-route, sparking a tense military standoff that left dozens dead and reignited troubling questions about security, separatism, and state failure in Pakistan’s most volatile province.

The ill-fated train, which had departed from Quetta on a long-haul journey to Peshawar, was carrying more than 400 passengers – among them women, children, and security personnel – when it was targeted near Sibi, roughly 160 kilometers from the provincial capital, Quetta.

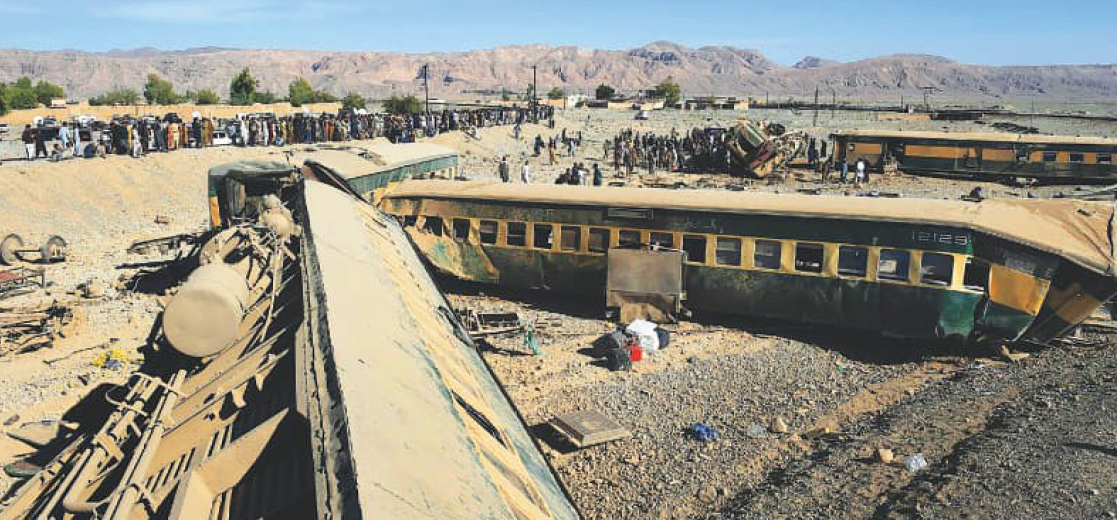

The attack took place at about 1pm, as the train traversed a mountainous stretch of the historic Bolan Pass, a region once carved into the landscape by British colonial engineers. Explosives were detonated to damage the railway track, forcing the train to a halt and plunging the passengers into chaos.

Initial reports indicated that dozens of passengers managed to flee, trekking on foot to the nearby Panir railway station, located six kilometers from the attack site. However, the majority remained trapped, as BLA fighters claimed control of the train, using hostages as leverage to make their demands known.

In a chilling communique, the BLA claimed responsibility of the attack and issued a 48-hour ultimatum to the government, calling for the unconditional release of Baloch political prisoners and those allegedly forcibly disappeared by the state. The group warned that any military operation in response would have ‘severe consequences.’

The state’s response was swift but bloody. What ensued was a full-scale military operation involving the Special Services Group (SSG), paramilitary forces, and the Pakistan Air Force.

Following the arrival of security forces at the scene of the attack, more than 50 additional passengers were safely evacuated, bringing the total number of rescued individuals to 127. By early Wednesday afternoon, government officials reported a steady increase in the number of those freed, with the tally climbing to 155. Within a few hours, the figure further rose to 190, marking a significant breakthrough in the ongoing rescue operation.

By the evening of March 12, the military declared the operation over. General Ahmad Sharif, the Director General of the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), announced the elimination of all 33 attackers. However, the victory came at a steep cost. At least 21 passengers were killed, alongside four paramilitary personnel.

Pakistani officials used a special freight train to move rescued passengers first to the larger Mach station, about 65km (40 miles) from Quetta and 90km (55 miles) from where the attack took place. At Mach station, passengers were given food and first aid. They have subsequently been brought by train to Quetta.

This was not the first time the Jaffar Express—named after a historical figure and connecting Quetta to Peshawar—has come under attack. In fact, the train has long been a favoured target for Baloch separatists due to its frequent use by military personnel and its symbolic significance as a link between Pakistan’s troubled peripheries and the state’s heartland.

In recent years, the BLA has ramped up operations, launching attacks on Chinese nationals, CPEC-related infrastructure, and state forces. But the hijacking of an entire passenger train marks a dangerous escalation, reminiscent of historical incidents far beyond Pakistan’s borders.

According to analysts, the BLA’s increasing sophistication and firepower reflect both strategic evolution and the state’s continued failure to address root causes of dissent.

‘The BLA has transitioned from hit-and-run sabotage operations to well-coordinated assaults,’ said Malik Siraj Akbar, a Balochistan expert based in Washington, D.C. ‘The train hijacking underscores their growing audacity – and the government’s inability to contain or track them.’

Rafiullah Kakar, a political analyst, specialising in Balochistan affairs said that the BLA has strengthened its command structure, giving fighters in the field more direct control over operations.

‘Additionally, access to advanced weaponry, some of which was left behind by US forces in Afghanistan, has enhanced the group’s firepower, making their attacks more lethal and sophisticated.’ Kakar further argued that the worsening security situation stems not just from intelligence failures but from a widening disconnect between the state and Baloch citizens.

‘Over the past decade, the province has become a laboratory for political engineering led by the military establishment, with six different chief ministers in 10 years, excluding caretaker setups,’ he said.

This instability, he added, has eroded democratic processes, undermining parliamentary politics as a viable means of political struggle.

‘The biggest beneficiaries of this growing state-citizen divide have been Baloch insurgents, who are increasingly able to recruit young men willing to embark on suicidal missions,’ Kakar said.

Akbar agreed, arguing that the state refuses to treat the Baloch population with dignity.

‘Islamabad relies on a provincial administration that acts as a puppet of the military, pushing propaganda to convince the world that there is no crisis in Balochistan and that the state remains firmly in control,’ he said.

Balochistan, despite being rich in natural resources, remains the least developed of Pakistan’s – provinces. Its 15 million residents contend with poverty, unemployment, and allegations of state-sponsored repression. Many in the region accuse security forces of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings – claims consistently denied by the government.

The ongoing China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), worth an estimated $62 billion, has added another layer to the conflict. While CPEC projects promise development, Baloch locals often complain of exclusion and exploitation. This perception has been skillfully exploited by insurgents to fuel anti-state sentiment and recruit disenfranchised youth.

Just last month, 18 soldiers were killed in a BLA attack in Kalat. Earlier in March, a female suicide bomber targeted law enforcement officials in the same region. These incidents, coupled with the Jaffar Express hijacking, point to a coordinated and rising insurgency.

While security forces were eventually able to regain control of the hijacked train, critics say the state’s reactive approach continues to backfire. In a report published in January, the Pak Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS) recorded a 119 per cent increase in attacks in Balochistan, with more than 150 incidents recorded last year.

Akbar said ‘Every time an attack happens, the state launches a military crackdown. But those operations often sweep up innocent civilians by linking them to the BLA or the armed rebellion without evidence.’

Moreover, most military personnel deployed in the province hail from other parts of the country, that’s Khyber Pukhtunkhwa and Punjab, which lack familiarity with the rugged terrain – an advantage insurgents have consistently exploited. Experts say there’s still time to reverse the downward spiral – but only if the state rethinks its strategy.

As survivors return home and families mourn their dead, the attack serves as a stark reminder of the cost of neglecting a region long pushed to the periphery of Pakistan’s national conscience. For now, the tracks may be cleared and the train may roll again – but the scars left behind will not fade so easily.

The writer is our Editorial Assistant and journalist.