Entangled, complicated mother-daughter relationships have formed the basis for many great writings. There is Toni Morrison with her book, Beloved, where the theme of generational trauma captures the mother-daughter relationship, layered with guilt and shame. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in her recent book, Dream Count, has also explored how expectations of mothers and cultural distance, particularly in diaspora societies, often complicate the relationship that exists between the mother and daughter.

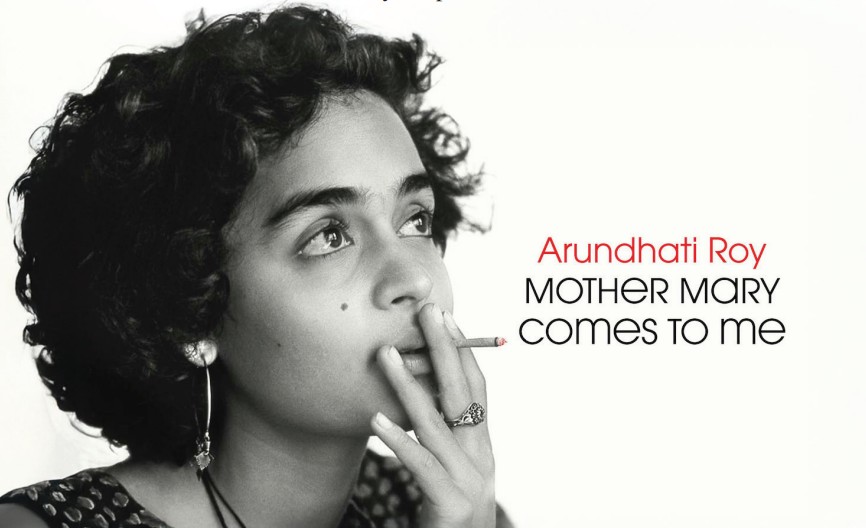

Pain, betrayal, emotional trauma, guilt, maternal ambivalence, intense bonding, and the striving for independence on the part of daughters are feelings portrayed plentiful in such novels. But perhaps no one can do this so beautifully, so simply yet in such a complicated fashion, as Arundhati Roy, through her memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me.

Pain, complexity, and ambivalence (as Roy writes, when referring to her mother, ‘She was my shelter, she was my storm’), it seems, provide the fodder for writers who write about this deeply painful subject. What particularly struck me about this particular book of Roy’s, who has mainly written political non-fiction, apart from her two novels (God of Small Things and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness), is her uncanny frankness with which she writes about her mother and their relationship.

After all, the memoir is not a piece of fiction, where the writer has the latitude for artistic license. Writers can retreat behind fiction and claim that none of this happened in front of the public eye, even though some of the characters and the narrative may draw themselves from real life. With memoirs, on the other hand, this choice does not exist. The writer confronts the reality head-on, deals with the pain of writing such an emotionally complex subject not only in private, but also in public. Roy admits it powerfully in the opening chapter of the book, ‘As a child I loved her irrationally, helplessly, fearfully, completely, as children do. As an adult, I tried to love her coolly, rationally, and from a safe distance. I often failed. Sometimes miserably. I wrote versions of her in my books, but I never wrote her.’

And does she write about her mercurial mother, with a sense of awe, fright, and love. Roy calls her a ‘gangster,’ after all, there are very few women in India who could boast of having a landmark legal ruling named after them. For it was Roy’s mother who filed against her community’s practice of granting sons a larger share of inheritance, which was overruled by a Supreme Court decision in 1986.

Roy also terms her mother a visionary for setting up a school in Kerala, which acquired a nationwide reputation. It was in this school that Roy also spent her formative years. What is astounding is that while her mother withheld affection from Roy and was downright cruel to her son, from ‘…the moment children entered the school, she became their mother, too. Not just figuratively, but literally.’ And this stands in stark contrast to how she was with her own children, as Roy terms it, ‘extremely bad-tempered.’ Roy almost apologises for her mother by saying that it potentially happened because of her mother’s bad asthma flare-ups or the medication that she was on to treat it. It is heartbreaking, however, when Roy writes in the book, ‘He [her brother] remembered our father and the big house we had lived in on the tea estate. He remembered being loved. Fortunately, I didn’t.’ For children to grow up without love and not know the feeling of being loved by their parents is truly frightening. But this is the beauty in Roy’s writing. With her usual candour, she ensures that the reader does not feel any pity towards her but rather attempts to empathise with her mother. After all, even if someone’s a ‘bad’ mother, it does not necessarily mean she is also a ‘bad’ human being. Or perhaps some people are not meant to be mothers in the worldly sense of the word.

This memoir, written with a brutally raw honesty, ought to be read by not only those who are already fans of Roy but also those who want to understand the complex psychological nature of mother-daughter relationships. Roy’s evocative prose was particularly appealing to me; her ability to craft complex ideas into beautifully structured sentences that catch one off guard.

From the very beginning, Roy captures the reader’s attention, weaving the narrative with the artistic flair that only she possesses. However, I could have done without some of the political musings, such as the dam issue and the Maoist uprisings towards the end of the book. The book then becomes less gripping because it starts talking more about systematic issues rather than the personal relationships that so far had been unearthed in the memoir. She returns to it eventually, allowing the readers to know what she stands for, about how her past has shaped her, and how it continues to influence her.

The writer is our Managing Editor and Assistant Professor at CBEC, SIUT