I have spent most of my adult life striving to bring together working people from across Pakistan’s many ethnic-national communities to build a viable left alternative to Pakistan’s militarised, bourgeois mainstream. This is no mean task in a society that is amongst the most classed, militarised and hate-riven in the world. The victimisation of working-class Pashtuns, Hazaras, and more under the pretext of deporting ‘illegal Afghans’ is the latest example of the acute divisions that run through the length and breadth of the Pakistani social formation.

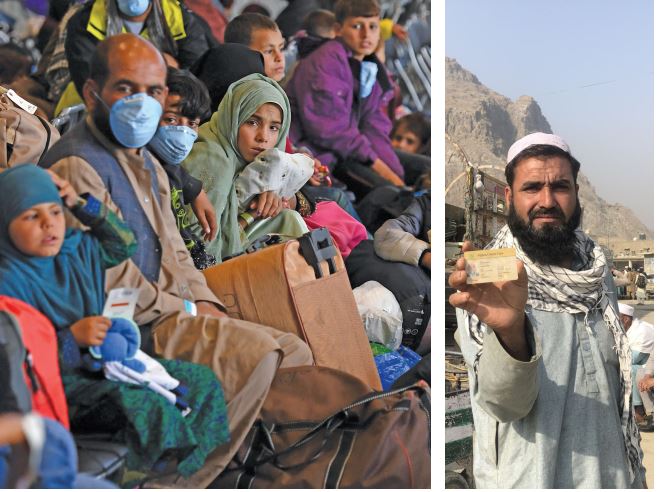

The abrupt decision of the ‘caretaker’ government to kick out almost 2 million ‘refugees’ is, in the first instance, a depraved attempt to scapegoat the victims of a disastrous 5 decade-old policy seeking so-called ‘strategic depth’ in Afghanistan.

The most recent iteration of the desire to simulate Afghanistan as Pakistan’s ‘fifth province’ was manifested only 2 years ago; Taliban rule had just been restored after the 20 year American occupation of Afghanistan and ex-ISI chief General Faiz Hameed landed in Kabul to lead Pakistani officialdom’s chest-thumping celebrations. Delusions of grandeur have since been predictably dashed – religious militancy has intensified in tribal districts like Waziristan and Kurram, while what our spymasters expected would be a ‘friendly government’ in Kabul has instead been keen to demonstrate that it does not sing to Rawalpindi’s tune.

Under this backdrop, the deportation initiative is a cynical distractionary tactic that makes the working poor and most vulnerable the fall guys for strategic games waged by unaccountable rulers. To be sure, official policy announcements of this nature largely affect toiling classes that can be easily targeted by a state apparatus that is trained in the most anti-people colonial tradition. The vast majority of people who have been protesting for weeks at the Chaman border, for example, are daily wagers. Meanwhile, big players in the highly lucrative cross-border trade of contraband, no matter their ethnic-national background, will continue with business as usual, especially those with close ties to the militarised state apparatus.

If the unending dreams/nightmares of ‘strategic depth’ are the immediate context for the deportation drive, there is a longer history at play which also begs attention. The so-called northwest frontier of the British Empire was, from the early 19th century, the staging ground for the ‘Great Game’, featuring, among others, Czarist Russia, Persian and Afghan kingdoms. The arbitrary drawing of the Durand Line in 1893 to separate Afghanistan from British India only heightened geopolitical intrigue, and the Raj proceeded to further militarise the ‘frontier’ after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

In a related vein, the British colonial policy infamously pitted the sub-continent’s ethnic-national and religious communities against one another. Most historical accounts of colonial ‘divide and rule’ policy tend to focus on elite segments. But the lowest ranks of the civil and military services, for example, were strategically staffed in ways that stoked ethnic-national and religious tensions in various parts of British India. This was particularly true on the ‘frontier’, and this policy has continued into the post-colonial period, particularly in the Baloch, Pashtun, and other ethnic peripheries.

The demonisation of Afghan ‘refugees’ has in fact brought into focus just how far the politics of hate has penetrated into the nooks and crannies of Pakistani society. This is most obvious in Sindh, where ‘Afghans’ – a deliberately nebulous category that can be easily conflated with Pashtuns – are widely blamed for taking away jobs and resources form Sindhi-speaking natives, whilst also threatening the latter’s demographic majority. It should not be forgotten that this tendency gained considerable ground during the governmental tenure of Altaf Hussain’s MQM, under the tutelage of the Musharraf dictatorship; the threat of ‘Talibanisation’ was widely cultivated in urban Sindh amongst Muhajir and Sindhi populations alike to demonise Pashtuns.

Over the past couple of decades, Balochistan too has been a site for growing tensions between Baloch, Hazara and Pashtun populations, as well as what are widely called Punjabi ‘settlers’. The gap between ethnic-national communities is not without a material context: Baloch nationalists are rightfully concerned about ‘development’ projects that are completely changing the ecologies, economies, and demographics of regions like Gwadar.

Indigenous communities around the world have legitimate reasons to resist reduction to a demographic minority – one need look no further than the historic dispossession of Palestinians by Israeli settler colonialism, but there are also many other examples, like the native populations of north America and Australia.

Just like there are progressive histories of resistance to colonial capitalism in many of these contexts, progressives in Pakistan have struggled to unite working people from ethnic-national communities. The 60s and 70s was the heyday of revolutionary internationalism around the world, and in Pakistan this was exemplified by broadly anti-imperialist and class political fronts like the National Awami Party (NAP).

Such political fronts came into being in the face of ethnic conflict, particularly in Sindh. The Pakistani state’s imposition of a unitary model of assimilation around the ideological pillars of official Islam and Urdu as exclusive national language was mirrored by urbanised and relatively educated Urdu-speaking migrants being given resources, jobs and political clout that antagonised ethnic Sindhis. But in spite of such divide and rule tactics, the left’s message continued to resonate. For the first few decades after partition, Karachi was the heartland of left wing politics, featuring a vibrant trade union movement bringing together workers of all ethnic-national backgrounds.

In recent decades, however, ethnic-national identity has been politicised in increasingly reactionary ways, especially as the power of financialised and military capital have reared their collective heads. The same Karachi that was the hub of socialist politics has been riven by violent conflicts over land that have been deliberately ethnicised by a combination of state functionaries, bourgeois politicians and economic mafias. Similar trajectories of politics, as I have already noted, have played out in Sindh’s other urban centres, as well as Quetta.

There is nothing progressive about scapegoating Afghan refugees and working class people hailing from ethnic-national backgrounds considered to be ‘non-indigenous’. Instead all progressives should take on the far bigger role played by the state and big capitalists like Malik Riaz in depriving local communities of resources, jobs, and dignity. What we need today, just as left-progressives understood in the earlier decades after partition, is a broad-based front of working people from all ethnic-national communities against land and other natural resource grabs by the nexus of capital and state.

It is, after all, the same nexus that forces working people from northern Pakistan – and indeed across the border in Afghanistan – to migrate away from their historical abodes so as to escape wars or survive economic hardship. Of course, developing a shared understanding is impossible in a social-mediatised political environment dominated by maximalism and hot takes. And it certainly is not what the militarised state apparatus and right-wing reactionaries of all stripes are interested in promoting.

But politics is the art of making what seems impossible into a real possibility. In months and years to come we can expect that the combination of rapacious capitalist profiteering and colonial divide and rule statecraft will reinforce the conditions in which the politics of hate takes root and thrives. The only hope of averting a rapid descent into barbarism is if progressives of all ethnic-national communities banish our demons and generate the collective will to build something different.

The writer is a teacher, author, and political activist.