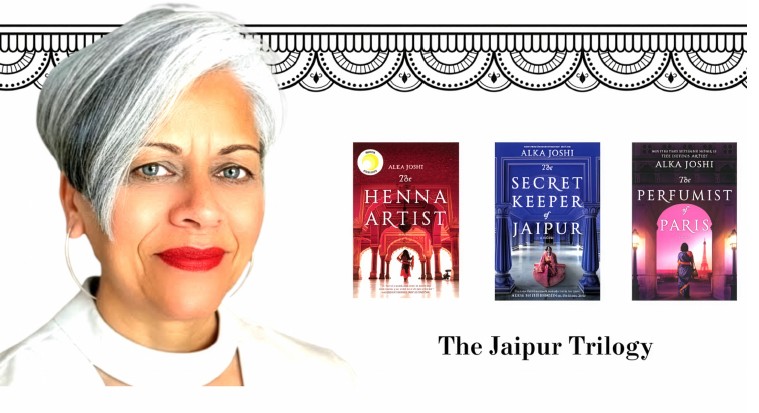

There is such sparsity of feel-good fiction from within the South Asian context that reading the Jaipur Trilogy on a colleague’s recommendation was a blessing. One either reads about the ravages of the colonial rule, or the wreckage caused by the partition, or if it is based in Pakistan, then the War on Terror occupies the imagination of writers. But the Jaipur Trilogy does not fundamentally center on any of these aspects. This series, a work of historical fiction, contains three books by the following titles, The Henna Artist, The Secret Keeper of Jaipur, and The Perfumist of Paris.

In fact, it provides a microcosm of the lives of people who are connected in different ways: a young woman, Lakshmi, who has run away from her abusive husband in the 1950s and seeks out to establish her own path first in the high society of Jaipur as a henna artist, and then eventually as a natural herb healer in Shimla. Then there is a mix of other quirky characters such as Malik who provide the readers an insight into another world. Readers also get a full account of Lakshmi’s sister, Radha (the third book centers primarily on her life) who develops her own path despite the odds stacked against her. There are different high-society characters, the social madams of the elite Jaipur society and their rich male counterparts who appear to have a cavalier attitude towards infidelity and marital affairs, to which the women in their lives turn a blind eye to.

Against such a backdrop, it feels like the Jaipur Trilogy is more like a soap opera: there is plenty of gossip, unwanted pregnancies, hushed-up abortions, pain of childlessness, clandestine romances across socioeconomic classes, a little bit of sex here and there, the grandeur of Maharani of Jaipur as well scandals and an accident cover-up. Do not read this series if you want a commentary on colonialism or gender discrimination. As I mentioned before, this is a feel-good fiction, with plenty of characters who keep you entertained in different ways. The prose is simple enough, with Hindi words here and there, along with a full glossary of terms translating Hindi words to English. I personally whizzed through this book because of the approachable writing style. For those who want to escape from their own lives and gain some hope and optimism for the future, then this book is it.

According to the author of the series, Alka Joshi, an American writer originally from Rajasthan, the character of Lakshmi is portrayed after her mother. Joshi has spoken about how her mother’s life story would have been different had she not gotten married at the early age of 17. And this is what makes the trilogy so relatable. Most women who dream of empowerment can understand Lakshmi’s desire for a ‘house of her own.’ Other women can connect with how its women, whether in Paris or Shimla, who are expected to shoulder the childbearing responsibilities. Others can also relate to the pain of betrayal at the hands of the beloved, similar to the one that Radha experienced in her almost childlike naivety. The classic mother-in-law and daughter-in-law tropes, typical of South Asian society, feature as well, although Lakshmi’s affectionate relationship with her mother-in-law stands out as something poignant.

And there are plenty of touching moments in the series, with the right kind of dramatic flair even though you know what to expect, especially, if you have read enough novels of a certain kind. But the post-colonial India that shows the physical remnants of the British rule, invoke a kind of nostalgia. The colonial buildings described vividly, and the upper class society with its association with the British as benefactors are also prominent aspects in the book.

And perhaps it is because of all the themes that the novels cover, that despite the predictable storylines, the trilogy has gotten widespread international acclaim, ranking one of the best sellers on the New York Times list. In fact, The Henna Artist has also been commissioned for a television adaptation although it currently still remains in production. Commentators have stated that this has the potential to become The Downtown Abbey for the South Asian region, which for those who do not have much affinity to read, would make it appealing.

A drawback about the trilogy is that nearly all characters receive some form of redemption, or at least get their own version of ‘happily ever after.’ Most of them escape largely unscathed, although, this probably says more about me as a reader, than Joshi as a writer. After all, happily ever after exists only in fiction. And this is what Joshi offers to us, a nostalgia, mostly cheerful, a lot of drama revisit of the 1960s India, coupled with scandals and romance.

The writer is our Managing Editor and Assistant Professor at CBEC-SIUT, Karachi.