You are too emotional, I don’t think you have what it takes to be a leader. These words uttered by a male colleague almost a decade ago still abuzz my ears. I am not quite sure whether he said that because I was a woman or because I was exhibiting traits like vulnerability and heightened sensitivity to emotions- the traits usually deemed feminine and hence, erroneously, taken to be subservient or non-rational. Was he merely trying to look out for me? I don’t really remember the focal point of the conversation during which he said it, but I do remember that it had a lasting impact on my confidence at that point in time, given the larger context of demeaning remarks, in the name of friendly banter, that he and his friends would often direct at me. I would often be tagged as highly sensitive if I resisted or tried to have a dialogue to reconcile what I thought were misunderstandings. I reserve the expansion on these points for another piece on the importance of cultivating higher education institutes as “caring spaces” rather than highly competitive entities for them to eventually be safe for everyone, however, for this one, it is enough to understand why it becomes paramount to understand the context of a situation to reveal how even seemingly benign acts can lead to unjust consequences. In this piece, I focus on how the very traits that were seen as my weakness and apparently blamed for a lack of leadership skills actually played an opposite role and aided in me leading huge multi-stakeholder relief initiatives in the highly unpredictable and stressful situation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Through this, I want to highlight why incorporating “care” into the ethics of leadership helps us move towards a more just future as a society.

I root my reflections in the moral and political philosophical perspective of Feminist Care Ethics, a perspective that takes the disposition and practice of care to be the fundamental unit of our social life and takes humans to be relational beings. Bringing attention to the fact that the values that are usually only associated with women are actually traits that make humans humane, it points to the importance of factoring them into our understanding of a just society. In this bid, it draws our attention to vulnerability, interdependency, relationality, responsibility, and responsiveness in a contextual manner to emphasize a relational understanding of our society and establish that care involves work, rational decision-making to make sure that everyone has a chance to flourish. When COVID-19 engulfed the world, this relational feature of society became starkly visible in how people banded together to help each other, even strangers in this time of crisis.

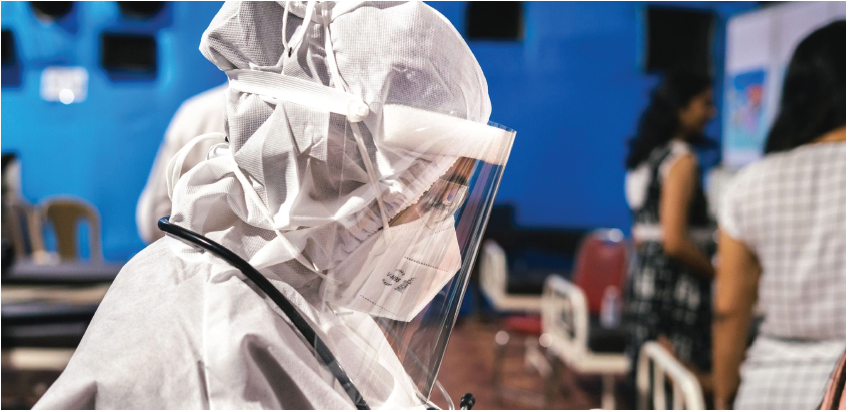

India was severely hit by the pandemic and to tackle the infection, a nation-wide lockdown was imposed in March 2020. On the one hand, for the privileged members of society it meant some time off from the daily commute to work, time to spend with the family, and to hone skills and hobbies; on the other hand, for the underprivileged section of society, especially the migrant daily wagers, it meant a complete stop to their earnings. Some of us students and teachers began providing the workers in our own institute with ration kits. I ended up managing this initial drive, and slowly my phone number spread far and wide. Once the initial group from my institute disbanded, and understandably so as the pandemic was a very emotionally and physically taxing time, I along with a few others could still continue working by collaborating with complete strangers. I could do so as we all had one thing in common: we all cared for our fellow citizens (a potential that feminist care ethics argues is present in all of us) and were also willing to take action for it!

Many of my peers were surprised, rather shocked, at how I could trust strangers reaching out for help for things ranging from food to medicines to house rent to even transporting them back to their villages across the country. But context mattered! Also, I could understand the vulnerabilities and limitations of both the people in need and the people in various government institutions that I was collaborating with while arranging ration, transport, quarantine facilities, etc. I could be an empathetic listener every time I received a frantic call for help. We all cared for the well-being of each other and worked with a spirit of collaboration rather than competition. I ended up working with some fantastic lawyers, researchers, activists, doctors, artists, community leaders, students, and even bureaucrats across the country. Navigating power hierarchies along the way, I also learnt a lot from the seniors. I was the youngest in the founding teams of almost all the initiatives I ran, still the skills I brought to the table were respected. Point is, we all could recognize our privilege, leverage it in the right way, collaborate and connect with people, and work towards providing a caring space to each other and especially to the marginalized, which led to successful initiatives. My being emotional and sensitive, always trying to understand the larger context, and attempting to maintain relationships across stakeholders came in handy. I am still in touch with people who I worked with in those two years of the pandemic, and we still run drives together during natural disasters or any other emergency cases. I am happy that I could put the ethics of care framework into the way I led these initiatives. Care and its associated values are not signs of weakness; rather they are the very tools that we need to combat crises and work towards a more just society where all can flourish.

The writer is a social scientist and philosopher and is currently a post-doctoral fellow at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay.

1 Comment

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

https://t.me/s/BEEfCasInO_OfFiCiAlS

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

https://t.me/officials_pokerdom/3096

This is such a good read. To keep care at centre, and allowing for leadership to be caring, can being about such a change. It’s good to see that unlike a lot of us, you could leverage this incident to do something more meaningful and beyond just you. I hope the network gets stronger and the values spread wider.