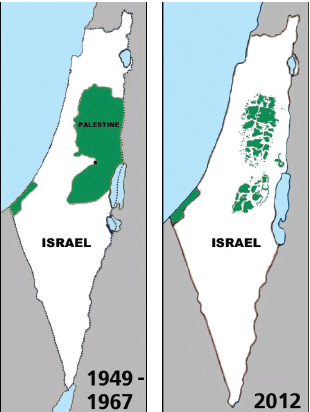

For many sceptics of the International liberal order in the Global South, South Africa’s case against Israel at the ICJ (International Court of Justice) was perhaps the first serious step taken by a state from there in the ongoing genocidal war against the Palestinians. A population occupied for decades, Palestine symbolises and inspires resistance against colonialism, remnants of colonialism/settler-colonialism, and Zionism.

In the application it filed in January 2024, South Africa accused Israel of failing to ‘prevent genocide’ and of ‘committing a genocide in manifest violation of Geneva Convention (1948, 1951)’. By then, according to the U.N.’s estimate, over 23,000 Palestinians had died in Israel’s attacks on Gaza. The number of Palestinian casualties has now crossed 35,000. These numbers (dismissed by Western journalists and commentators as ‘Hamas numbers’) along with the visuals of war – circulated by IDF soldiers, Palestinians journalists and humanitarian workers on social media in which Palestinians homes and bodies, dead, alive, and captured, are openly violated and disparaged – have sparked moral outrage across the globe. The response at the United Nations ranged from the usual paralysis-by-veto in the Security Council – as the US unreservedly protected Israel through its veto power – to performative resolutions in the General Assembly. Even though diplomatically isolated, Israel, the US, and their European allies all ignored these resolutions. Such spectacles are not new for the people looking at the U.N. from the Global South, who have been periodically witnessing, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the abject failures of the U.N. in one crisis after another.

The response of Muslim and Arab states to the relentless Israeli assault on Gaza was, unsurprisingly, morally compromised and politically defunct as well. Most of these undemocratic repressive regimes (Pakistan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Libya, Kuwait, UAE, Qatar, and so on) are heavily dependent on the US for their military and (in some cases) economic security and as such, the security of their regimes. It was, therefore, South Africa that undertook moral leadership in the Global South in bringing the Israeli brutal war on Palestinians to the scrutiny of the international law and put the current liberal legal order to the test. We have yet to see how the ICJ, and the international legal order it draws its legitimacy from, responds to this challenge.

In analysing South Africa’s case against Israel, many commentators have aptly invoked statements of solidarity by anti-Apartheid South African leader Nelson Mandela and drawn parallels between the Palestinian struggle against the occupation of their land and the struggle to end apartheid in South Africa. It is worth expanding upon this particular historical context of third world solidarity as well as of early decolonisation, in terms of anti-colonial struggles and its impact on issues of human rights and self-determination at the U.N. These struggles were brought together by newly independent Asian and African states at the U.N. They condemned apartheid and Zionism in the same vein.

Revisionist scholarship on the history of international human rights suggests that issues like ‘the self-determination of peoples and racial discrimination’ became important issues in the Commission on Human Rights at the U.N., once the newly independent states had joined the organisation, where they were particularly active between the 1950s to the 1970s. The Bandung Conference (1955) and the Tehran Conference (1968) are important milestones in this story of third world solidarity, even as the participant states’ contradictory Cold War alliances were on display. Many anti-colonial leaders, such as Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) and Jamal Abdul Nasser (1918-1970), were prominent participants with influential intellectual and political presence at Bandung

Anti-colonial in their pronouncements and invoking human rights throughout the Conference, powerful figures like Nasser, however, repressed dissent in their own countries. Human rights featured in the closing session of the Conference as well, where the head of the Pakistani delegation, Prime Minister Chaudhry Muhammad Ali, too spoke of human rights, stating ‘the people of Asia and Africa … stand for the fundamental principles of human rights and self-determination’. Ironically, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, and Turkey had joined CENTO (Central Treaty Organization) a few months before Bandung (in February 1955) and were busy supressing communist parties and workers at home. The Communist Party of Pakistan had already been banned and a Communist-inspired coup had been crushed in 1954. Communism was seen as another form of imperialism by US aligned states like Pakistan, and thus spoke Pakistan’s Prime Minister at Bandung: ‘we must be very careful … that we are not misled into opening our doors to a new and more insidious form of imperialism that masquerades in the guise of liberation’.

Apart from the anti-Communist vitriol by states like Pakistan, issues of state sovereignty and non-interference were central to the postcolonial states’ understanding of the global order at Bandung, and were perceived in uneasy relation to the universal ideas of human rights; however, even as the anti-colonialist notions underlying human rights and how they served the right to self-determination were not lost on the newly independent states, they were cautious of interference in their sovereign lands in the name of securing those very rights. This tension was exacerbated as many of these states descended into their own political and economic crises, and by Tehran 1968, the universality of human rights had given way to a cultural relativist perspective on human rights. At the subsequent nonaligned summits of the 1960s and 1970s, human rights had receded to the background.

So, it should not be overlooked that Bandung constituted, if only for a brief moment in history, a clear example of third world activism in international politics.

Nonetheless, Western powers saw the coming together of Asian and Arab states at Bandung with alarm, as a threat to Western influence and as a form of ‘communist engulfment’. Several states at Bandung and later in Tehran (1968) had either ignored or downplayed Communist incursions into Asia (Korean War 1950-53) and Europe (Hungary 1956). Also of serious concern to the Western imperial perspective was the tying together of Zionism with apartheid. It was the issue of self-determination and national liberation that had ideologically linked Asia to Africa and imperialism and colonialism to Zionism and apartheid. At Tehran (1968), apartheid and Zionism were denounced together. Syrian diplomat Adib Dauody candidly laid out how Arabs and Africans saw these connections: ‘It was high time that Africans and the Third World became aware of the existence of an unholy alliance between world imperialism, European colonialism and the racist entities established in the Asian and African countries’. The Saudi Arabian delegate too ‘denounced the collusion between Zionism and apartheid’ and highlighted the similarities between Southern and Portuguese Africa and the occupied territories’. Saudi moral and political inaction towards the suffering of Palestinians in occupied lands today stands in stark contrast to the stance it and other Arab states took then.

The South African case against Israel at the ICJ is a reminder of the impact that third-world solidarity can make within the global liberal order. The caveat here is, of course, that the ANC-led government, despite all its shortcomings at home, can claim to represent its people and their anger at what has been unfolding over the last six months in Gaza and for decades in the occupied Palestinian territories. Many Muslim and Arab states have failed this test miserably, and even as they unabashedly claim representation, the levity of those claims at home and on the global stage is clear for all to see. What is needed in these states is a ruling class that does not lack political courage, moral integrity, and diplomatic finesse, and which can, above all, forge global solidarities to resist the bloody forms of settler-colonialism and neo-imperialism with the strength of the Global South.

The writer is a political and legal anthropologist.