Alison Klayman’s ‘Paramount AI Weiwei: Never Sorry’ (2012) deals with two issues that are akin to the current global conjuncture, the emerging interest of artists in radical art activism and the use of digital technologies for a more dynamic and interactive form of filmmaking. The documentary follows the story of Ai Weiwei’s everyday struggle against state authorities, who are constantly harassing the artist to give up on his ambition for free speech. As the story proceeds we see how the thin line dividing art from all other aspects of life slowly dissolves into politics, as the central subject of the artist. Later on, as the documentary proceeded the work of art became so immersed in the subject that politics became an art form for Ai Weiwei. Thus, his famous slogan which he borrowed from the various 20th century movements such as the Dadaists, Surrealists, and later the Situationists, defines his work, saying ‘Art is political. Everything is political’.

At the heart of Alison Klayman’s documentary is this radical dictum ‘the incarnation of disruptive documentary activism in the digital age for global social justice movements.’ This activist documentary argues that the capacity of disorderly documentation to impact and motivate self-organised mobilisation can be observed in the activist practices of Ai Weiwei against the Chinese authorities in subtle ways that only artists of that caliber can do. They cannot be seen as an isolated event but are closely connected with the emphasis on hooliganism as an effective contagious encounter, within anonymous masses in both physical and virtual realm.

Alison’s documentary filmmaking is more about art activism under constant surveillance and threat to life itself. It is also about the rise of hooligans as a re-invented form of art activism. In ‘Never Sorry’, Klayman tells the story of Ai Weiwei through visual hooliganism in a way that defines both its subject and interpretation of the act of hooliganism. The documentary itself speaks and captures Ai Wiewei’s activism in such a way that shows how the instrument of control and surveillance of the communist party in China can be inverted as a tool of resistance. Many of his contemporaries in the global art scene speak about Weiwei’s artivism. ‘He turned himself into a hooligan to deal with the organised state hooliganism’.

‘Hooliganism’ in this context is defined as a method of disruption and anarchic tactic which is, confronting and at the same time deceiving the Beijing authorities who harass Ai Weiwei for speaking about what he thinks makes the fundamental of modern polity. Following the documentary, Klayman seems to be fearless like his subject and follows just like what Weiwei has followed through his art form. Hooliganism is seen as a form of unruly documentary artivism that has become prevalent in the digital age of globally mediated social justice movements. It is a tool for resistance used by both Ai Weiwei in China and the Turkish protesters during the Gezi protests.

The ‘Occupy Gezi’ movement, within a brief span, gave rise to a distinctive ‘network culture’ featuring participatory media, civil journalists, alternative computing specialists, hacktivists, and other actors. These diverse contributors coalesced around anarchic forms of civil disobedience, later pejoratively labeled ‘çapulculuk’ (looting or vandalism) by the government. Subsequently, protesters were derogatorily termed ‘çapulcu,’ often translated as ‘looter’ or ‘thug’ by international media, but a more nuanced interpretation, such as ‘hooligan,’ aligns with the charges of hooliganism leveled against art activists like Ai Weiwei, Pussy Riot, and Femen for comparable public protests against repressive governments.

Ai Weiwei’s hooliganism, in the context of documentary artivism, blurs the boundaries between art, politics, and mediation, reflecting the complexity of aesthetic styles and influences in the documentation of social movements. The self-proclaimed hooliganism of Ai Weiwei and the Turkish protesters demonstrates their defiance against government incrimination and their ability to turn negative labels into a means of resistance. Hooliganism operates within the framework of virality and memetic thought contagion, as proposed by Tony D. Sampson’s theory, which explains how ideas and political gestures spread in the digital age. Hooliganism, as a form of documentary artivism, plays a significant role in allowing communication, forming alliances, and reflecting an art activist impulse with contagious influence during social movements like the Gezi protests.

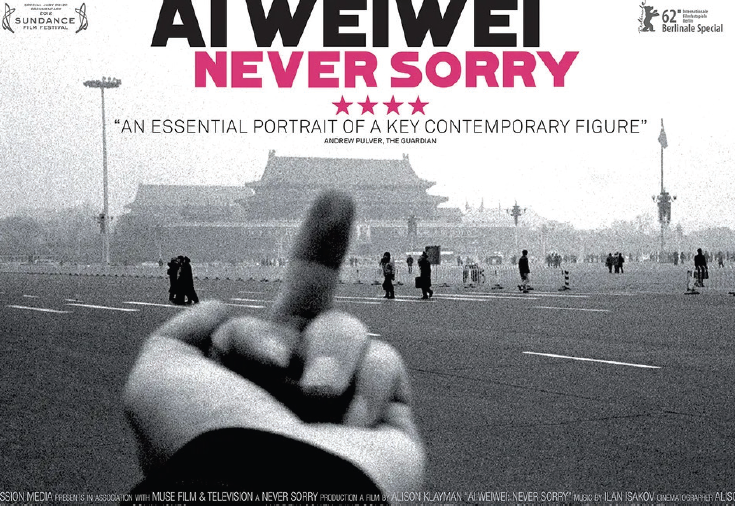

‘Tactical media’ is another expression that is akin to artivism although it stresses more on the expressions of dissent that rely on artistic practices. As the documentary filmmaker, Alison accepted the Sundance Film Festival’s special jury prize, she raised her middle finger in salute to the Chinese artist’s unwavering resistance against the Chinese government.

Imitating and embracing one of Weiwei’s most famous controversial gestures.

By doing this Klayman has turned herself into a witty apologist, while the title of the film itself recourse to the unapologetic stance of contemporary artivism towards cultural transgression. It also makes the film function as an apology in the classical sense, registering a case for the artist against Chinese’s government.

This modern form of apologia has larger significance for documentary studies in that it provides a starting point to understand the broader context in which particular activist discourses like hooliganism and culture jamming gain prominence, calling for a reconsideration of the ethical boundaries of documentation in the twenty-first century.

To draw parallels between Ai Weiwei’s art activism in China, as documented in Alison Klayman’s film ‘Never Sorry,’ and the Gezi protests in Turkey, which were documented and disseminated and went viral through the Internet. It proposes Tony D. Sampson’s theory of virality and its application of Dawkins’s neo-Darwinian memetic thought contagion model to understand how ideas and political gestures spread in the digital age. It highlights the lasting influence of early independent documentary films, such as Global Uprisings’ ‘Taksim Commune’ and Capulling Sinemacilar’s ‘Gordum I Saw,’ in establishing an audiovisual aesthetics of revolt in Turkey.

Alison Klayman’s acceptance of the Sundance Film Festival’s Special Jury Prize, where she imitated and embraced one of Ai Weiwei’s controversial gestures, inadvertently turning herself into a witty apologist for hooliganism and culture jamming.

The documentary does not provide an in-depth analysis of the specific limitations of Ai Weiwei’s art activism. It does not explore alternative perspectives or criticisms of the concept of hooliganism as a form of documentary artivism. The potential ethical implications of using viral dissemination and memetic thought contagion in the context of social justice movements. It does not address the potential biases or limitations of the documentary film “Never Sorry” in portraying Ai Weiwei’s activism. Klayman’s does not engage with the broader scholarly discourse on the relationship between art and politics, beyond the specific examples of Ai Weiwei.